Rapper Swaggy Gzz poses with a friend in front of the Lakeview Apartments in White Plains, NY. (Credit Chioma Nwana)

As a teenager, Tajay Dobson dreamed of becoming a star, and for the last three years of his life, he was one. He had become TDott Woo, an entertainer and rapper in the hip-hop style known as drill, and even created a signature dance, the Woo Walk. He performed it in the music video for “Welcome to the Party,” the platinum-certified single that cemented late rapper Pop Smoke as a New York drill music powerhouse.

Although his videos went viral and he had Woo Walked across some of music’s biggest stages, Dobson didn’t have a record deal until Feb. 1, when he signed with the label Million Dollar Music. But just hours later, Dobson was gunned down in his neighborhood in Canarsie, Brooklyn. He was 22.

“My son was the life of our family. He was around for everybody,” said Robert Dobson, Tajay Dobson’s father. “But his career was taking off, and [some people] just don’t want to see somebody else shine. Why do these kids believe that violence is the answer to everything?”

Since Dobson’s death, at least six other prominent drill artists in New York have been victims of firearm homicides. The youngest was just 14 years old.

Some government officials and members of law enforcement have pinned the latest wave of gun violence on the emergence of drill, a subgenre of rap that has become notorious for its hyper-specific, actionable descriptions of violence. In their songs, some rappers went as far as name-dropping to whom they would do harm or even murder.

During a February press conference, Mayor Eric Adams called for accountability from drill rappers and the social media companies that give them a platform to “over-proliferate violence in [their] communities.”

The New York City Police Department also has officers monitoring social media platforms. Detective Gary Allen is a community affairs officer who conducts online investigations on musicians with potential connections to crimes. “We watch all the music videos, and then we get on social media and put two and two together,” Allen said. “We build a case, and we get a subpoena from the judge to use that [information] against that person.”

While Ivie Ani, hip-hop and culture journalist and media personality, acknowledged that there may be some truth to certain rappers’ lyrics. She also suggested that many investigations into their music lack nuance and ignore context.

“Rappers are the only musicians who don’t get the benefit of the doubt when it comes to their type of storytelling. Their type of imagery—the hyperbole they use—is always always deemed reality when, in a lot of cases, it’s not,” Ani said.

But Allen, the NYPD detective, believes it’s better to be safe than sorry. In 2014, pioneering Brooklyn drill rappers Bobby Shmurda and Rowdy Rebel and more than a dozen other members of their gang, GS9, received a 69-count indictment, which included charges of murder, assault, weapons use and possession, and narcotics sales. Many of those charges were a result of Allen’s colleagues’ submission of Bobby Shmurda’s quintuple platinum single “Hot N*gga” as evidence. Its lyrics contained several descriptions of illegal activity, such as the song’s most popular line, “Mitch caught a body ‘bout a week ago.”

“No matter how you look at it, we’re telling you what’s going on,” said Sb Swavo, a 20-year-old rapper from the Lower East Side who was previously investigated by police. Some of his friends have been killed by gun violence, and he explained that despite what lyrics suggest, some rappers use music to get people’s attention.

“[We’re] just trying to make it out [of our neighborhoods] and get away from all this,” Swavo said.

Drill music was born in the South Side of Chicago between the late 2000s and the early 2010s. It was pioneered by young Black rappers entrenched in local gang culture, whose narratives became anthems of disenfranchised and disillusioned youth, and it has spread to not only New York but around the world.

Kyle Holody, a professor from Coastal Carolina University who studies the effects of the media, said that the nature of drill music could be described as a righteous anger or a justified response to systemic oppression.

“I don’t want there to be violence,” he said. “But sometimes, that’s the only message that will be heard.

Ahiela Watson, a former youth advocate at the New York Urban League, pointed out that many of the musicians being blamed for the violence in their neighborhoods only carry and rap about guns because they themselves are afraid to die.

“Nobody knows who’s [going to die] next,” said Watson. “Structural violence has been perpetuated against us for centuries. Why should anyone be surprised when that violence bleeds into our communities?”

Gabe Pabon, the host of On The Radar, a Power 105.1 hip-hop radio show, has become an older-brother figure to many rising drill stars, and said that the issues are much deeper than just lyrics in songs.

“People love blaming the kids, but they’re just talking about what they’re going through in real time,” he said. “Blame the system.”

A handful of drill artists don’t just rap about their circumstances; they also work in community development. EA Thomas, president of Winners Circle, a record label co-owned by major New York City drill artists like Sheff G and Sleepy Hallow, said the label recently launched its own nonprofit called the Winners Win Foundation. The aim of the nonprofit is to give back to the community—especially the youth—through local activations such as food drives, student grants, and music events.

“A lot of our youth are displaced and seeking a sense of community,” said Thomas, who feels that some of the issues that people associate with drill music actually stem from a lack of community. “Some aren’t in school. Some don’t even have home addresses. For some kids, community can be found in music. A subset of that is hip-hop. A subset of that is drill.”

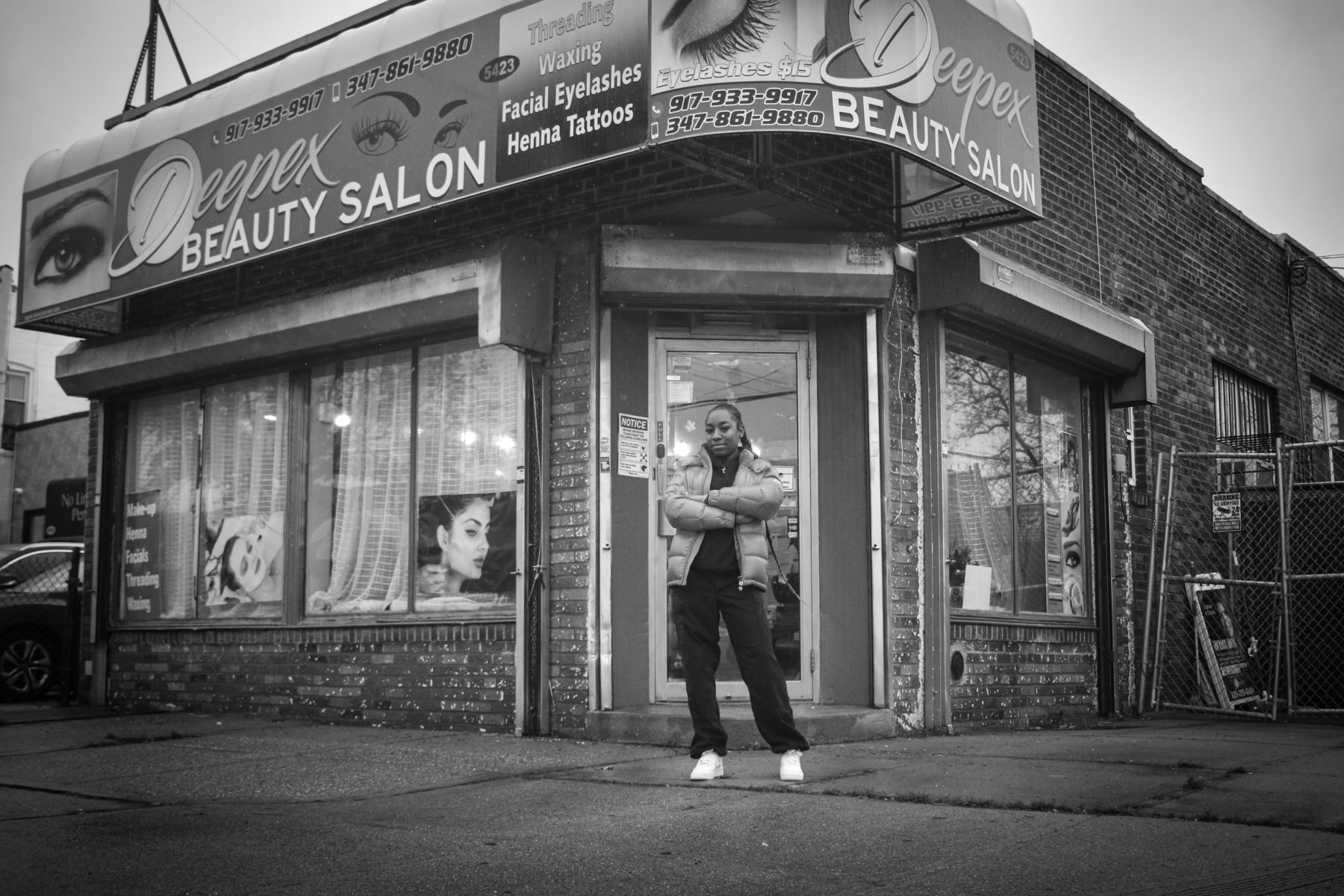

Rapper Tianna “Titi” Dobson poses in front of the Deepex Beauty Salon in Mill Basin, Brooklyn. (Credit: Chioma Nwana)

For other artists, making drill music is community service. Tianna “TiTi” Dobson, Tajay Dobson’s younger sister, said she hopes to use her music to change the public perception of drill culture and humanize the artists comprising it. “Everybody thinks, ‘[drill artists] are just gang members,’” she said. “But they’re people.”

In July, the 18-year-old released her debut single, “Situations,” to honor her late brother.

“I wanted the entire world to know my brother is a human being,” she said. “I don’t want them to think that him dying from a gunshot defines him. He’s a star.”

Correction: A previous version of this story misspelled Tajay’s first name.

About the author(s)

Chioma Nwana is a freelance writer and photojournalist focused on music, culture, and community.