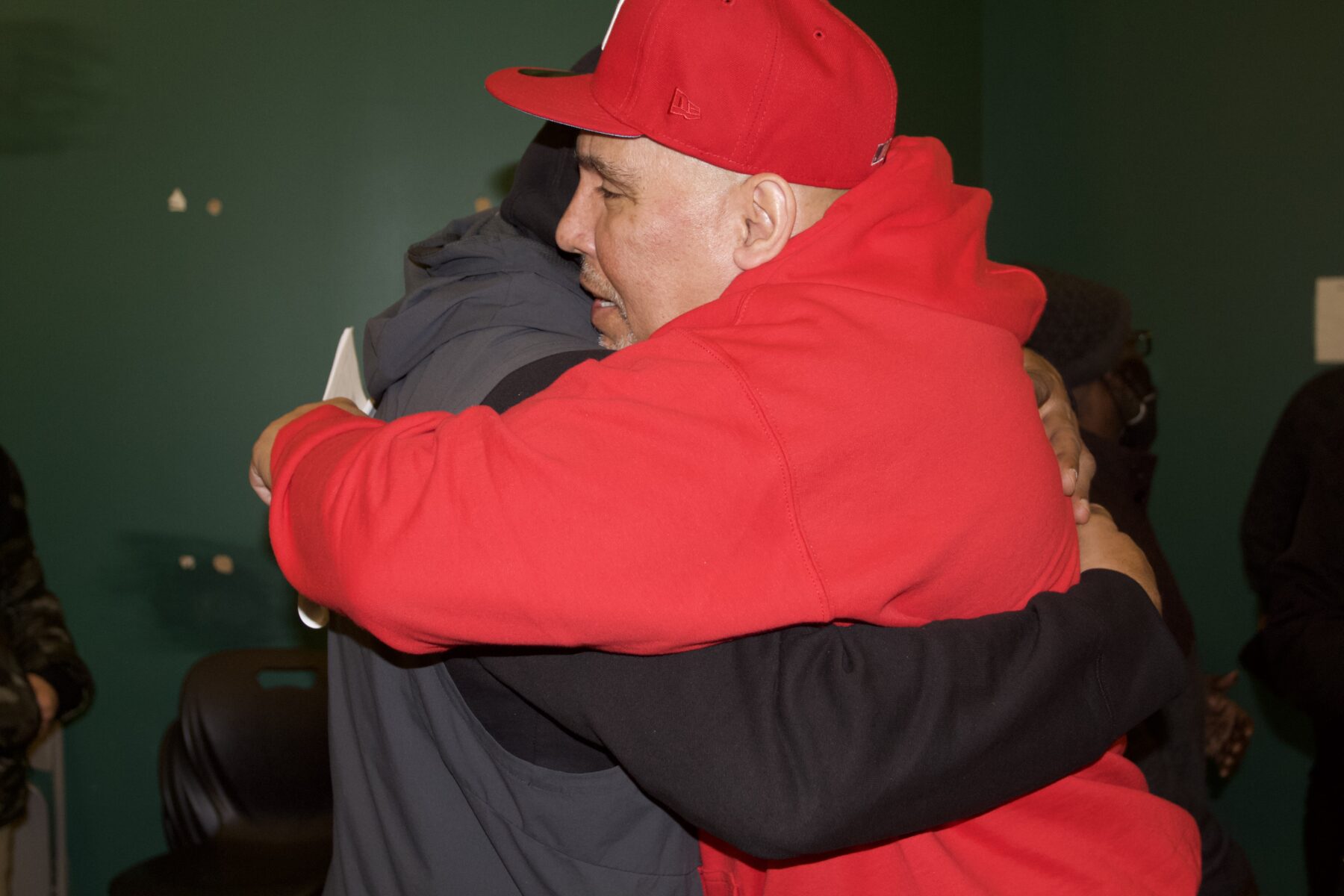

Edwin Ortiz and a member of the Returning Citizens Support Group hug during a session (Credit: Indy Scholtens)

Adnan Khan remembers being woken up in the middle of the night in mid-January 2019 by a prison guard in San Quentin State Prison. He was told to pack his belongings. Despite initially protesting — he thought he was being moved to a county jail — Kahn complied. Moments later, he was in court, where, after 16 years in jail, he was declared a free man. He was released after California Senate Bill 1437 changed the law that put Khan in jail for a murder that he did not commit.

“All I heard was gasps and cries in the background,” Khan said. “I could not believe it.”

Khan was 18 when he participated in a robbery during which his accomplice stabbed a man to death. Although Khan did not commit the stabbing, and knew of no intent to kill anyone beforehand, he was sentenced to 25 years to life for felony murder.

“It was supposed to be a snatch and grab,” Khan said.

The reason Khan was given such a long sentence lies in the rules that define felony murder. Although the exact terms of the rules differ in each state, they all say that anyone involved in a felony can be held accountable for murder if someone dies during, or because of, the crime – even if the accused played no direct role in the killing or the planning of it.

Now a bill in New York might change the law.

The felony murder rule originated in England in 1716, but was abolished by the United Kingdom in 1957 because there was little support for the law and it failed to diminish felonies or felony murder. The United States and most states in Australia are the only countries in which the rule is still applied today. Hawaii and Kentucky abolished the felony murder rule. Other states, such as Illinois, Minnesota and California, have reformed the way the felony murder law is stated because an increasing number of people nationwide are questioning whether it is just to similarly punish someone who directly killed someone, and someone who contributed to the crime, or the planning of the crime, but had no role in the killing.

In prison, Khan taught himself about the felony murder rule and started working in criminal justice reform.

“The only way for me to go home is if we change this law, otherwise I’m probably gonna die in here,” he said, describing why he started learning about the law.

Khan worked with among others the Anti-Recidivism Coalition and his own organization, Restore Justice, to gather data on people convicted for felony murder. The results revealed that many serving lifelong sentences only played a minor role in the felony. The groups shared the data with Senator Nancy Skinner. Senators Skinner and Joel Anderson introduced Bill 1437, which proposed changes through which a defendant was required to play a more direct role in the killing. The bill was signed into law on September 30, 2018. The felony murder law changes took effect in California the following January 1, allowing those with minor roles in a felony resulting in death to be resentenced. This resulted in 602 individuals to be resentenced between 2019 and 2022; these people collectively saw a reduction of 11,353 years in prison, according to L.A. Times reporting at the time. Khan was resentenced to three years for robbery, and since he had already served more than five times this sentence, he was released without parole or probation.

Currently, a New York bill, similar to the California bill, is in the Assembly, and if passed and signed into law, could lead to the release of those who played a minor role in the felony. However, there is no indication on how many the law could affect, because there is little data on this group. The Felony Murder Reporting Project, an independent research project, has so far identified 226 people incarcerated for felony murder in New York, and found that Black people are 19.1 times as likely to be incarcerated for felony murder than white people.

“The law is designed to marginalize Black and Brown people,” said Carmelo Ortiz, 57, who spent more than half of his life in prison.

In New Jersey, the felony murder rule is folded into the definition of murder in the first degree, meaning that people who commit felony murders will be given the same sentence as those who premeditated a murder. This is the rule that put Carmelo in prison.

Carmelo and his brother Edwin were 20 and 18 years-old when they were both convicted of felony murder and sentenced to 30 years in prison in New Jersey. They committed a robbery in 1986 that turned fatal. Carmelo was the getaway driver. His brother was the one that fired the gun.

“I thought the jury would find me not guilty of the murder because I was the getaway driver,” Carmelo said.

Carmelo and Edwin were born in Puerto Rico, but grew up in the notorious Christopher Columbus Projects in Newark.

“There were no doctors, police men or professionals to look up to,” Carmelo said. Instead, they grew up surrounded by crime. Carmelo wanted to be a boxer and trained – determined to go to the Olympics – because he was inspired by Muhammed Ali. But when the boxing center burned down, he ended up on the streets. Both brothers sought escape from domestic violence through drugs, and both got addicted as teenagers. By the time they committed the robbery, resulting in their incarceration, they used crime to support their addiction, they said.

Both brothers turned their lives around in prison, they said. They served their sentences and were released in 2016. The two now run a reentry program in Newark for formerly incarcerated people returning to civilian life, a project they see as a way of offering redemption for the victim of their robbery, and of helping people and giving back to the community. Nevertheless, Carmelo is critical toward the racial bias written into the law that put him in prison for more than half of his life.

A report released in January 2023 by the New Jersey government, supports Carmelo’s criticism: although Black individuals represent just 15.4% of the state’s population, according to Census data, 59% of the 13,196 incarcerated individuals were Black.

In California, Black individuals, while making up for 5% of the state’s population, account for the 42.7% convicted for felony murder, according to research by the Special Circumstances Conviction Project, a project that collects and analyzes data from California’s criminal justice system.

“The felony murder doctrine is a vehicle used to impose extreme sentencing, particularly to young people of color,” said Nazgol Ghandnoosh, a researcher for The Sentencing Project.

Another aspect of the felony murder law that often receives criticism is its role in mass incarceration. A study published in March 2022 by The Sentencing Project found that the felony murder charges are often used by prosecutors to obtain plea deals for lengthy sentences.

From the 236 persons incarcerated currently for felony murder in New Jersey, 37 are sentenced to life. The remaining people, on average, serve a sentence of more than 26 years. And in California, more than half of the 5,000 individuals that are serving life without parole are there due to a felony murder conviction, the 2023 report by the Special Circumstances Conviction Project states.

“It has a major impact on the prison-industrial complex, [and] it’s a major driver of mass incarceration,” New York Assemblymember Robert Carroll said.

Carroll is seeking to reform the felony murder law through a bill he introduced last February. The legislation proposes changing the law to apply only to defendants who have directly caused a death or who were an accomplice to premeditated murder. The bill also proposes the option to resentence those unjustly convicted under the current felony murder law.

“Even if, for actual killers who killed unintentionally during, say, a robbery, a significant penalty is deserved,” said Guyora Binder, an expert on felony murder and a law professor at SUNY Buffalo Law School. “That does not say that an equal penalty is deserved for accomplices.” Binder added that more than half the people convicted of felony murder did not actually murder anyone.

The bill states that the current felony murder rule must change because it makes no distinction between intentional and accidental murder, the approach disproportionately affects young, non-white people and victims of domestic violence, and it allows those involved in a felony to be sentenced for death caused by a third party.

A third-party murder is the circumstance that put 29-year-old New Yorker Jagger Freeman in prison. In February 2019, Freeman helped organize a robbery of a T-Mobile store in Richmond Hill, Queens. When the police caught Freeman’s partner in the act, he drew a fake gun. The police opened fire and accidentally killed their own detective, Brian Simenson. Although Freeman was neither in the store nor even carrying a weapon, he was still found guilty of felony murder. In July 2022, he was sentenced to 30 years to life in prison.

Freeman’s case received a lot of attention at the time and inspired Carroll’s bill. If it passes he is likely to be resentenced. Nearly a year has passed since the bill was introduced, however, and there is no guarantee it will pass.

Carroll said that like all major reforms of criminal justice, it does not happen overnight. In the meantime he and his co-sponsors are trying to get more attention from advocates and other Assemblymembers. “Until we see it start moving, we can’t rest,” Carroll said. “But I’m optimistic.”

The District Attorneys for the Bronx, Brooklyn and Manhattan declined to comment about Carrol’s bill for this article.

Khan, meanwhile, still cannot believe he is out of prison. After several years, he shifted from prisoner advocacy work to film. He now has a residency with San Francisco Film for 2023-2024, a nonprofit organization that supports independent filmmakers. Khan is also a co-writer for a show about a formerly incarcerated Californian. Although he said there is not much he can share already about the project, he said that a lot of it is based on his own life.

“There is a character that came home after a felony murder [sentence],” Khan said. “I do want to continue my advocacy on awareness around that.” Khan said that the media has a big influence on shaping the public opinion about laws such as the felony murder law and often contributes to fear mongering. He wants to change the way the media portrays incarcerated people and thereby change the public perception. “I mean, we went in as teenagers, as kids,” Khan said. “A lot of us, we learned how to shave in prison.”

Khan said his life was forever changed by the felony murder rule.

“Committing a robbery is absolutely wrong and I still carry responsibility for that,” he said. “But I don’t carry responsibility for other people’s actions.”

Correction: A previous version of this story incorrectly noted the year of the robbery that Carmelo and Edwin Ortiz participated in; the robbery occurred in 1986.

About the author(s)

Indy Scholtens is a Dutch journalist and graduate student at the Columbia Journalism School.