Broadway in Washington Heights. Credit: Mariam Lobjanidze.

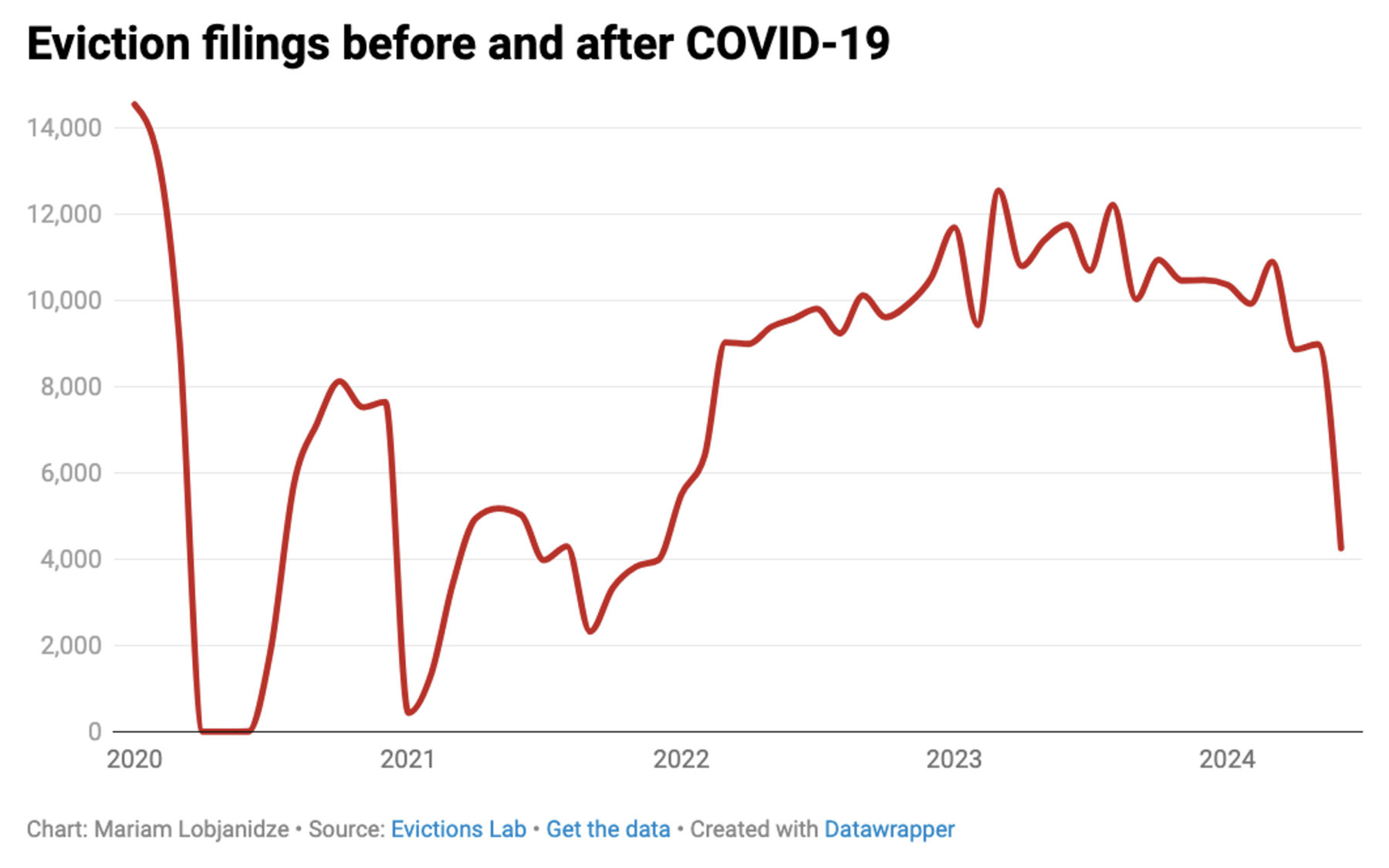

Eviction numbers are down in New York City compared to pre-pandemic numbers.

There have been about 125,000 eviction filings across five boroughs in the last year, which is only 55 percent of the historical average, according to Peter Hepburn, a sociologist and data scientist at Princeton Eviction Lab.

One of the contributing factors to the decrease is that New Yorkers who are 200 percent below the poverty line now have the right to counsel meaning that they can be represented by lawyers, which helps tenants navigate the court system. New York City was the first city in the country to implement this law in 2017 in a very small number of zip codes, which expanded in each borough over the years. Since executing evictions takes time, the city is seeing the effects of the law post-pandemic.

“It [the right to counsel] means that tenants have rights that they did not have five or six years ago,” Hepburn said. “But it also means that the process takes longer because the smaller number of [eviction] cases that were filed in 2022 will result in an even smaller share of executed evictions.”

In addition to the right to counsel, the city also received COVIDRRP—rental assistance from the federal and state governments—during the pandemic.

During the pandemic, there was a state-wide and federal level which slowed eviction proceedings. Despite the moratorium, eviction rates were not zero, as the law had exceptions, according to Hepburn. When eviction filings started back up again in 2021, there was a long backlog of cases that had come to the courts before and during COVID-19.

In census tracts where Hispanic and Black people are the majority race of renters, eviction rates returned fastest to the pre-pandemic levels.

In census tracts where Hispanic and Black people are the majority race of renters, eviction rates returned fastest to the pre-pandemic levels.

In New York City, only white, Black or Hispanic can be a majority race of the renters in a census tract. Among them, the number of evictions in white-dominated areas has dropped the most; in 2023, it only accounts for 37 percent of the total number of evictions in 2019.

For areas where tenants are predominately Black, the eviction number of 2023 is about 60 percent of 2019. The rate is 76 percent where Hispanic tenants predominate, more than twice that of the white race.

According to Hepburn, the racial disparities in eviction rates have existed for a while now.

Hispanics have the greatest eviction filing rate in 2023, which is twice and three times higher than that of White and Black people, respectively, according to the evictions lab data.

Based on their analysis of eviction filing rates, all three races have a similar decline of about 50 percent compared to the average filings in 2016 through 2018.

“While there were significant gains during the pandemic [in marginalized communities in the form of rental and legal assistance], they did not erase preexisting racial disparities,” Hepburn said.

The biggest racial differences before and after COVID-19 seem to be in the process from filing to execution. Eviction filing is a legal step before the eviction execution, which is decided by the housing court hearing.

In marginalized communities with a higher concentration of Hispanic or Black renters, higher execution rates have been observed, even with free legal assistance.

Data analysis for 2023 shows that while Hispanic and white tenants see a correlation between execution rate and filing rate, the linear relationship seems to break down in areas with the most black tenants.

Washington Heights. Credit: Mariam Lobjanidze.

According to Patrick Boyle, senior director of the New York Market Office and Community Enterprise, eviction filings rarely lead to evictions, which is why more evictions get filed than actually get executed. He added that landlords file for evictions because they want to push their tenants to seek resources so they can pay rent.

Boyle said that filing for eviction expedites the process of reaching payment agreements between the landlord and the tenant. This is because sometimes tenants are not responsive unless their case ends up in the housing court or they don’t know how to apply for government resources.

“It’s not a good system,” Boyle said. “I mean, we should not have eviction filings happening just to get people the help they need.”

He also added that owners in affordable housing are not seeking to evict tenants.

“These owners, there’s no benefit in them for evicting the tenant because the housing that they rent out,” Boyle said. “It’s going to be affordable to another low-income person afterward.”

He added that the imperfect system makes nonprofit housing organizations more important because they are trying to provide support and resources for people in a more upstream way and without necessitating eviction filings which clog up courts.

Among the resources available to people is One Shot Deal, a program that helps New Yorkers pay their rent and bills if they are experiencing a job loss or an unexpected medical situation.

Oksana Miranova, a housing policy analyst from Community Service Society, said that another reason why eviction rates are lower now is because of the passage of the Housing Stability and Tenant Protection Act in 2019, according to which “Owners may no longer apply a 20 percent increase to an apartment rent upon vacancy.” As a result, landlords have fewer incentives to evict tenants who cannot pay rent.

“With the passage of the HSPPA, uh, that pressure [to have a high tenancy turnover] was removed a little bit just because they’re no longer able to add on rents,” Miranova. “It doesn’t mean that landlords don’t want to evict their tenants in certain situations. It’s just like there’s less of an economic incentive to do so.”

The trend moving forward that Miranova pointed out was the fact that since the pandemic there has been an uptick in evictions for people who are moderate income and above the poverty line.

“Low-income people, even though logically, they would be more vulnerable to evictions, they get resources, they get right to counsel,” Miranova. “So they’re a little bit less vulnerable to evictions compared to maybe people who are sort of like in the middle.”