PRINCETON, N.J. — Lisa Ferguson received the call on the morning of September 1, just as her Labor Day weekend was getting underway. It was from a social worker at the Princeton Care Center, the nursing home where her 80-year-old mother had been living for nearly five years: “I have some difficult news for you. The center is shutting today. Your mother is being moved to another facility by the end of the day.”

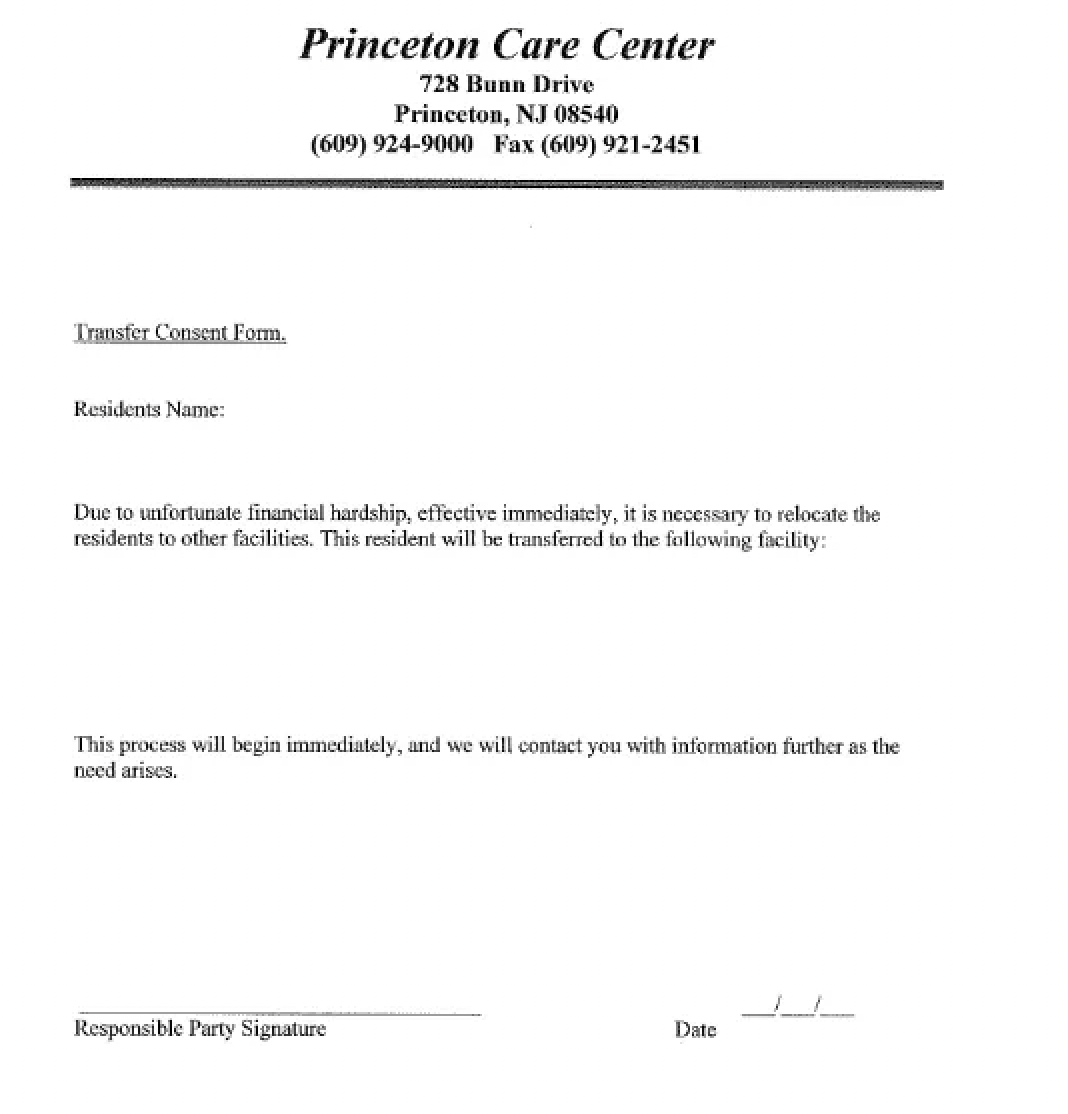

Ferguson was then emailed a short, blunt “Transfer Consent Form,” which read, “Due to unfortunate financial hardships, effective immediately, it is necessary to relocate the resident to other facilities.” It gave no details where her mother, Florence Edwards, would be transferred.

Nora Mikalson, left, and Florence Edwards at their new nursing home in Lawrenceville, N.J. (Credit: Oishika Neogi_

Like relatives of many of the other 71 senior Princeton Care residents, Ferguson rushed to rescue her mom, who suffers from diabetes, glaucoma and arthritis. What she found, she said, “was utter chaos.” The water was turned off, and many seniors hadn’t been offered food since breakfast. With little help, families had to quickly empty their loved ones’ rooms and pack their belongings. Using garbage bags, laundry baskets and wine boxes, they furiously piled together everything from clothes to knick-knacks to medications.

Ferguson eventually transferred her mother to the Clover Meadows Healthcare and Rehabilitation Center by 7:30 p.m. Friday, about 10 miles from the Princeton center. “By the time they (patients) reached the new facility that evening, they were soaked” in urine, she said.

Ferguson and other relatives eventually received an email from Ezra Bogner, administrator of the Princeton Care Center. It was as blunt as it was opaque: “Due to unfortunate financial hardships, effective immediately, we are initiating a plan to relocate our residents to other facilities with the resources to meet their immediate needs.”

Bogner also stated that “our staff members continue to care for our residents with compassion, competence, and dedication” — at the same time that his administrators wanted residents out of the building by the end of the day. Bogner did not respond to multiple requests by phone and email for comment.

In fact, the center has been in trouble for some time. Just weeks earlier, the state Department of Health issued a devastating report about conditions at the center. After an intensive three-week survey, inspectors found 27 deficiencies, ranging from insufficient staffing to failure to adequately administer dialysis to residents suffering from kidney disease. “Three of the 27 deficiencies constituted substandard quality of care in the areas of freedom of abuse, neglect and exploitation, quality of life and quality of care,” the state found. Inspectors also insisted that the center admit no more patients.

More than a dozen families said they weren’t sent the report and didn’t know how bad things had gotten — from health or facility officials. “Wasn’t it the state’s responsibility to let us know of the conditions in which our relatives were living?” said Avani Patel, granddaughter of a resident at the center. “I don’t think they are completely blameless.”

Employees knew that the center had been deteriorating for some time. “If we’re being completely honest, we should have seen this coming,” Susan Kalitan, director of activities, said in an interview. “We should have seen this coming from the day our checks began bouncing” last month.

“There was a lack of milk, food, diapers” — even toilet paper, said Kalitan. “Paychecks to vendors were bouncing, and basic bills were not being paid.” Garbage accumulated around the building as its administrator had not been paying for pickup, she added.

Kalitan said she is owed $3,923 for three weeks’ work. She has filed for unemployment with the state. Her assistant, Connie Mekae, said she is due about $2,000.

Other employees were as stunned as the families. “I was not informed of anything,” said Ethel Terkings, a 71-year-old certified nurse aide who had worked there for 30 years. “I only found out what was happening after I showed up at the center on Friday morning.” Speaking of Bogner, she said that “the least he could have done was look us in the eye and tell us the truth. Even if the truth was that we just did not have jobs anymore,” Terkings said. She noted that she is owed $2,500, and her $1,000 monthly rent is now overdue.

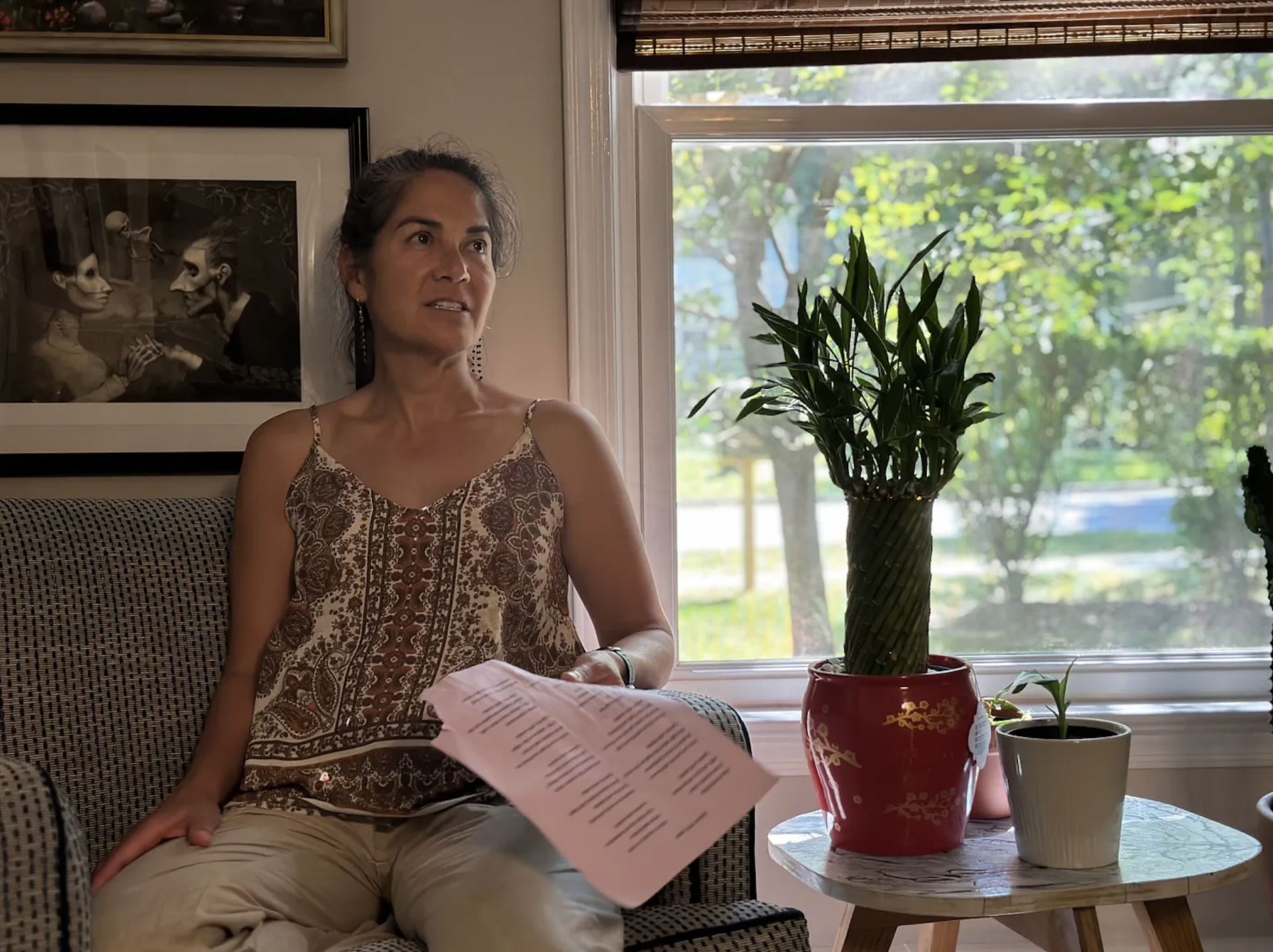

Lisa Ferguson explains how she coped with the “chaos” at Princeton Nursing Center. (Credit: Oishika Neogi)

Municipal officials were told of the problems a few weeks ago. “We had said numerous times throughout the month that there should be a mandate that the facility notify people of the problems there and let them know of the possibility that the facility could close,” Mayor Mark Freda told the Princeton Planet, a local news site. “But the Department of Health said there was nothing it should be doing ahead of time.”

The center was established in 1985 by William Bogner nearly three miles from its current location, where it moved in 2004. After he died in 2016, his son Ezra took over as administrator.

In 2021, over a span of seven weeks, the federal Medicare program issued nine fines to the Princeton Care Center. It couldn’t be immediately determined what prompted the fines, which totaled $17,568.

Ethel Terkings, an employee at Princeton Care Center for 30 years, collects her belongings on Sept. 3, 2023. (Credit: Oishika Neogi)

The center’s closure has disrupted the lives of patients and their families. Sorat Tungkasiri, who works at Princeton University (which is unaffiliated with the center), was in New York City when he got the call about the shutdown. “I asked if I had a choice in the matter. I was just told ‘no,’ and the call hung up.” His mother, a 80-year-old Alzheimer’s patient, was moved to a nursing home in Morristown — 36 miles from Princeton. That facility is owned by Allaire Health Services and is a nursing home where other patients were relocated, according to families.

Nora Mikalson, who was recently diagnosed with lung cancer, was sent to Clover Meadows Healthcare and Rehabilitation Center. She, too, had seen signs of trouble in recent months.

“There was a difference in the way we were fed,” Mikalson, 72, said as she recalled smaller food allotments, and being served milk in plastic cups instead of full containers. The lack of staffing was a constant concern; she said she saw a wheelchair-bound patient fall down the stairs one day when no one was watching out for her.

Families are also wondering about their loved ones’ “personal needs allowance” bank, which represented funds that they accumulated so patients could buy items such as clothing, books and toiletries.

Tungkasiri’s mother, Chuanpit Pattasin, had as much as $4,754 in her allowance account, he said. And he doesn’t know how to access the funds.

While some patients are confused, others, like Mikalson, are fully able to understand the chaos that the forced move brought. As she sat on her wheelchair in an open area in the new nursing home, she said, “I’m not going to die of cancer; I’m going to die of a heart attack because of all this.”

Peter Saalfield contributed to this report.

About the author(s)

Oishika Neogi is an investigative journalism student at Columbia Journalism School. She focuses on human rights and identity politics stories.