Maria Castrillo remembers the day murky flood waters began to climb over her porch. Its sprawl seemed never-ending.

On September 2, 2021, it had rained relentlessly for two days. Just past midnight, she stepped outside her rented home on South Main Street in Manville, NJ. The water was rising on both sides of the street. An unoccupied police SUV was parked at the street corner, its blue and white lights flashing to caution traffic about the deep puddle. She checked the situation three hours later. The water was still on the rise.

“I knew it was coming,” she said.

The rain was from Hurricane Ida. Up and down the east coast, from Sept. 1 to Sept. 2, several observatories in Northern New Jersey recorded over nine inches of rain.

Rainwater typically runs off into local streams that then merge into rivers. The water level rose, resulting in a costly flood and over $2 billion of immediate damage in the State of New Jersey. While the longer-term cost of recovery was hard to quantify, New Jersey residents still feel its impact today.

The borough of Manville, which thrived during the 1930s as an industrial town, is situated right next to the confluence of the Millstone River and the Raritan River. On that day, rainwater overwhelmed the two rivers, with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) recording the crest reaching over 27 feet – the highest they have ever detected at this location. Any crest, the agency said, exceeding 20 feet would result in widespread flooding.

Around 6 a.m., Castrillo’s husband woke her up.

Glancing through the window, she spotted floodwaters filling her backyard. Fearing the flood might escalate, the couple roused their two children, hastily packing four backpacks with as many clothes and essential items as they could fit. The water had crept up to their doorway, so they escaped through a window and fled to the park across the street.

“We were like on an island,” she described the flood water coming to her family from all directions.

Flood water reaching the front porch. (Credit: Courtesy, Maria Castrillo)

Later in the day, they heard the veterans’ center nearby had transformed into a shelter, so the family walked there. When they made their way to the shelter, they observed the streets covered in brown deluge.

Escaping the flood was a traumatic experience for Castrillo, and many other New Jersey residents who, like Castrillo, are still balancing their family’s income and expenditure. The complicated and slow recovery system has frustrated residents like Castrillo, while leaving the flooded communities unprepared for the next disaster, which could come any day, as the state is again in the middle of hurricane season.

A struggle to pay the bills

With financial assistance from local programs, the family stayed in a one-bed hotel room for a year. Then, they landed in a four-bedroom apartment for $2,400 per month, $600 higher than the rent of their flooded home in Manville.

With the increase in rent, there was little leftover for the family to balance their budget. Castrillo’s husband earns about $1,800 each month. Castrillo occasionally worked as a bartender, earning about $130 per night, but business took a massive hit during the pandemic. Even in the best of times, she was only bartending once or twice per month. She receives disability aid for depression and has been diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder from the flood, she said.

In addition, Castrillo said, the family receives food stamps each month. Castrillo also frequently has food drives and food banks to stock up their fridge.

The most challenging part, she said, was replacing the clothes and other necessities they had lost in the flood. Clothes drive events help, but items like furniture are harder to come by.

“I just want to be able to save again,” she said.

“Aids cannot cover all losses caused by a disaster”

Immediately after the flood, Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), a federal agency dedicated to helping survivors prepare and recover from all disasters, offered Castrillo two months of rental assistance for $4,374, and an additional $3,971.10 to replace her lost property. She received another $2,467.44 in lodging reimbursement in Oct. 2021.

FEMA reported in Sept. 2022 that $873.6 million in federal funds have been provided for New Jersey to recover from Hurricane Ida. Within these funds, about $253 million were approved as disaster assistance aid for about 45,000 households in the state, roughly $5,622 for each household. The State of New Jersey also allocated other funds for residents, the most recent instance including $228.3 million of federal Community Development Block Grant Disaster Recovery (CDBG-DR) funds put toward helping residents rebuild their homes.

The fund, though, isn’t enough.

“FEMA Assistance is not a substitute for insurance and cannot cover all losses caused by a disaster; it is intended to help with emergency disaster recovery needs,” FEMA wrote in its notice to Castrillo.

Additionally, the intricate application requirements for these programs can prevent individuals in need from receiving the funds. In June 2023, she received a phone call from FEMA stating that her claim for the Tenant-Based Rental Assistance Program (TBRA) had been rejected. This was the second denial of rental assistance for her family. They also faced rejections for medical aid and funds related to moving and storage.

Castrillo said that the agent informed her that they were unable to clearly read the lease she had uploaded.

Before submitting the claim, she had made multiple calls to inquire whether the agency would accept a photo of the lease instead of a scan. The agents said that it was acceptable.

“If they had informed me, I would have paid to have it scanned,” she lamented. Instead, she had opted to take a photo using her phone.

Because of this rejection and delay, she missed the deadline for resubmitting the application. While FEMA has not disclosed the exact amount of compensation applicants would receive, she said that one of her neighbors had been granted approximately $30,000 for house rental expenses over the past two years.

Flood Insurance: the imperfect answer

“Flood insurance can be the difference between recovery and financial devastation,” FEMA states on its National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) website. All homeowners and tenants are eligible for the program.

FEMA actively maintains a Flood Insurance Rate Map (FIRM, or Flood Map), which “defines both the special flood hazard areas and the flood zones applicable to the community.” The special flood hazard areas, also known as 100-year floodplains, have a higher risk for flooding. In communities that participate in the NFIP, all home and business owners with structures in high-risk areas who hold mortgages from federally regulated or insured lenders are required to buy flood insurance.

Flood risk exists even for homes located outside the designated flood plain, the agency says. Climate change has contributed to such uncertainty.

However, NFIP’s current authorization will expire on Sept. 30. If not reauthorized by Congress, FEMA will stop selling and renewing the policy.

Castrillo’s home was outside special flood hazard areas. She wasn’t required to purchase flood insurance, even though FEMA estimated a chance between 1% and 0.2% for her home to be flooded.

A study published in 2020 by Jake Bradt, Carolyn Kousky, and Zoe Linder-Baptie from the University of Pennsylvania estimated based on 2018 NFIP enrollment data that the flood insurance take-up rates can exceed 75% for tracts that border the ocean, but are much lower away from the coast.

The study attributed low take-up rates in regions not mandated to purchase flood insurance to a combination of poor understanding of the risk, failure to realize the role of flood insurance in recovery, as well as the belief that the insurance is too expensive, and/or budget constraints.

Among all the valid registration for Individuals and Household Programs after Hurricane Ida, less than 8% of all the NJ residents who reported to FEMA that their home was flooded said they have flood insurance, according to FEMA data.

Cleighton Smith, the borough’s floodplain manager, estimated that more than 500 buildings were flooded in the borough of Manville alone. He said there were many uninsured survivors in the area. Some could not catch up with their mortgage.

Richard Onderko, the Mayor of Manville, said there are still more than a dozen homes left abandoned because their owners cannot afford to rebuild these properties. He said Federal Recovery programs could have helped these homeowners rebuild their homes.

“The flood recovery programs were a disaster,” he said.

A struggle to catch up with mortgages

Other families covered by the program also claim the payment they received from claims is of no match to the loss they experienced.

Ashley Avila purchased her dream house in Highland Park, a community that also sits on the bank of the Raritan River, for $860,000 in July 2021. Her home is right next to Mill Brook, a small stream that merges into the Raritan River a few miles away.

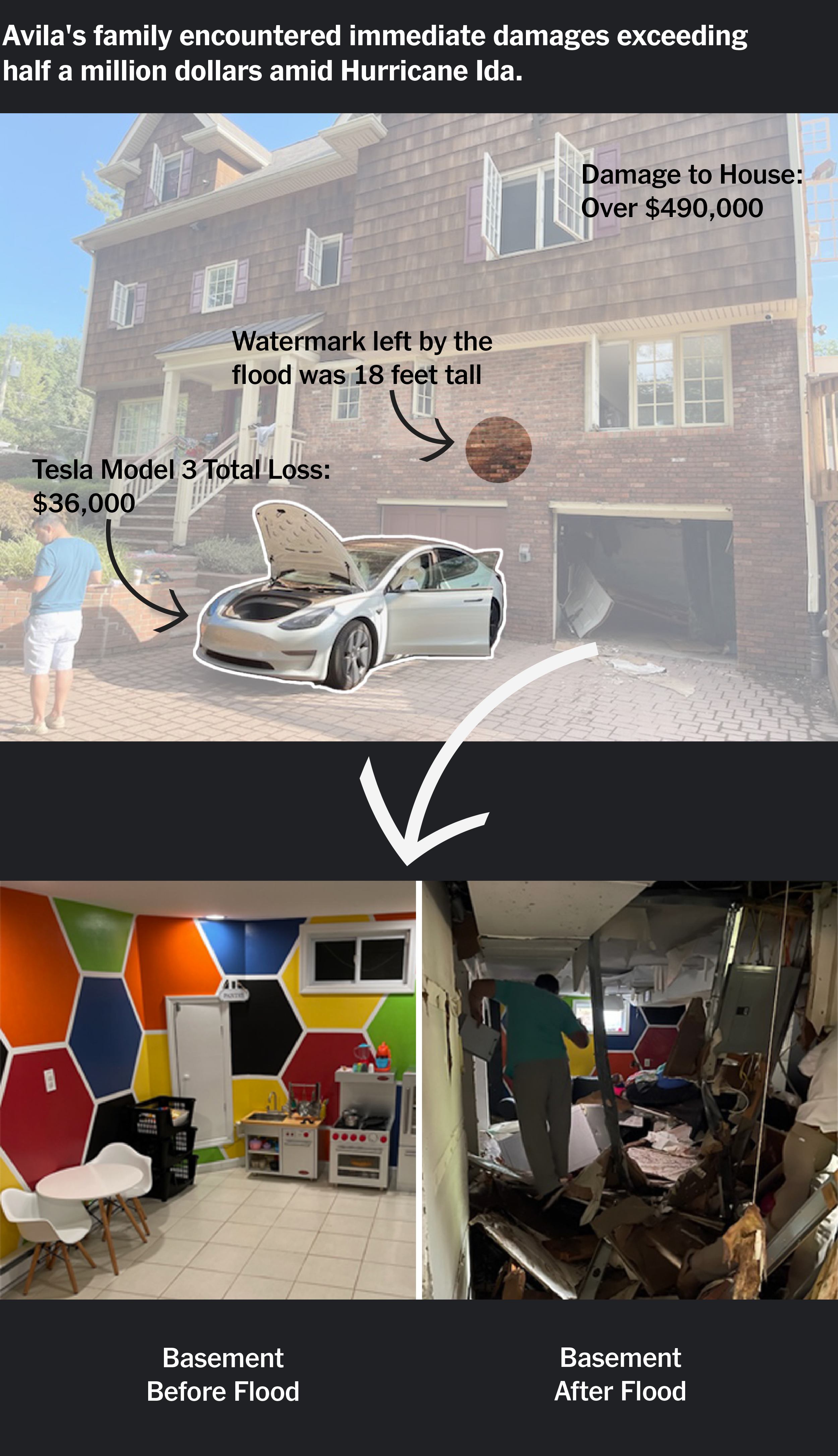

Two short months later, many of her family possessions were washed away by 18 feet of flood water coming from the brook. Her husband’s Tesla was totaled, and her contractor estimated the family had to spend $497,000 to repair their house, more than half of the property’s worth.

Her flood insurance policy covers up to $250,000 for building damage, and up to $60,000 for personal property except for vehicles. However, her initial quote was $98,000.

To purchase the home, Avila’s husband participated in the veteran home loan program, a program that helps veterans with no down payments and lower interest rates. Now, they are still about $90,000 behind their mortgage. If they do not catch up with the payment by September, they might end up in foreclosure and lose their house and lose their privilege for the loan program permanently.

“It’s not like we’re not paying our mortgage deliberately,” Avila said. “We need a place to live, we need a place for our children to live. And the house is not livable. There’s no running water, there’s no electricity, there’s no gas, there’s nothing.”

In the past two years, the family moved between four rental homes, Avila said. The rent of these places was about $4,000 each month.

Her children also took on the heavy burden of adapting to the new environments as they had to transfer between four different school districts.

“If you would have met my then three and four-year-olds,” Avila said. “The first words out of their mouths were ‘Did you know that our house was destroyed? The water took everything.’”

Voluntary buyouts

Even with flood insurance to protect the financial security of the homeowners, houses in the flood plains are likely to be flooded again, putting properties and lives at risk.

Smith, Manville’s floodplain manager, said the borough went through five major floods before Hurricane Ida, with the earliest record dating back to the 1950s.

As upstream communities began to urbanize, the farmland that once surrounded Manville became rooftops and parking lots, making rainwater runoff into the rivers faster during severe storms. This causes more severe flooding.

Since the late 1990s, FEMA started a series of programs to buy out flood-prone properties from owners and restore the land to open space. Blue Acre, the lead house buyout program in New Jersey, has purchased more than 1,000 properties since its launch.

“Blue Acres’s mission is to move households out of harm’s way by buying out their flood-prone, flood-damaged houses, and to preserve the vacated lands as flood storage buffers against future flooding,” said Alvin Chin, a Blue Acre program specialist. The program is part of the State’s Climate Change Resilience Strategy, which aims to improve the resiliency of these communities as the effects of climate change worsen.

In addition to offering the residents living in a flood-prone property a new start, Kathyrn Balitsos and Garin Bulger, researchers at the New Jersey State Policy Lab, Rutgers University, wrote in a lab report that buyouts can also offer opportunities to restore the floodplain, providing greater flood protection for the surrounding areas.

Blue Acre has bought out more than a hundred properties in Manville since the 1990s.

After Hurricane Ida, the program requested $10 million of federal funds to buy out 31 properties in Manville in Aug. 2022. The fund was approved in December, but the money has not been given to the Blue Acre.

In December 2022, Blue Acre expanded its program to encompass other boroughs. They submitted a list of 96 properties, including Avila’s home, to FEMA. The program sought $40 million in federal funds to acquire these properties at their pre-flood assessed values, averaging around $410,000 each.

FEMA responded via email that the request is still under review as of Jul. 27.

To expedite the process, Blue Acre resubmitted the request in June, temporarily halting the application process for about 20 homes from the list.

Chin, a specialist from Blue Acre, explained that all these homes are located in Manville. The New Jersey Office of Emergency Management (NJOEM) is working on a house elevation program for these properties. This program aims to reduce future flood damage for participants by elevating their homes a few feet above the ground.

These two programs will collaborate and provide guidance to homeowners, helping them weigh their options and choose between buyouts and elevation options. This strategic approach ensures that the funds are used as efficiently as possible, returning properties with the highest flood risk to open space.

Although there is no estimated timeline for when funds will be disbursed for these properties, Chin stated that the buyout process will proceed rapidly once the funds become available.

Two years later, families are looking for a fresh start

Still, the wait might turn out to be too long for Avila. The Blue Acre program cannot buy her property if it is under foreclosure. The family moved to Florida last year, where their rent is half of what they paid in New Jersey.

“It’s a new beginning for me,” she said. “All the other stuff, it’s just stuff, it doesn’t mean anything at the end of the day, because they could just be taken from you so quickly… Everybody was okay, we got out safe. That’s the most important thing to me.”

Castrillo, on the other hand, stayed in New Jersey, her home for over 30 years. She knows what she wants next: to apply for housing aid, support her family, and obtain a college degree in nursing.

Both families now live away from the Raritan River.

For more information, including the source of data and analysis, please visit this GitHub page.

About the author(s)

Hongyu Liu is a data journalist and M.S. student at Columbia Journalism School.