Ahmed Mohsan Mohsan at work, grilling lamb and chicken. (Credit: Mukta Joshi)

Ahmed Mohsan’s profile picture on WhatsApp is an American flag in the shape of a heart. When his youngest daughter was born, he wanted to name her America. The hospital attendant chuckled at him. Ahmed ended up naming her after his sister.

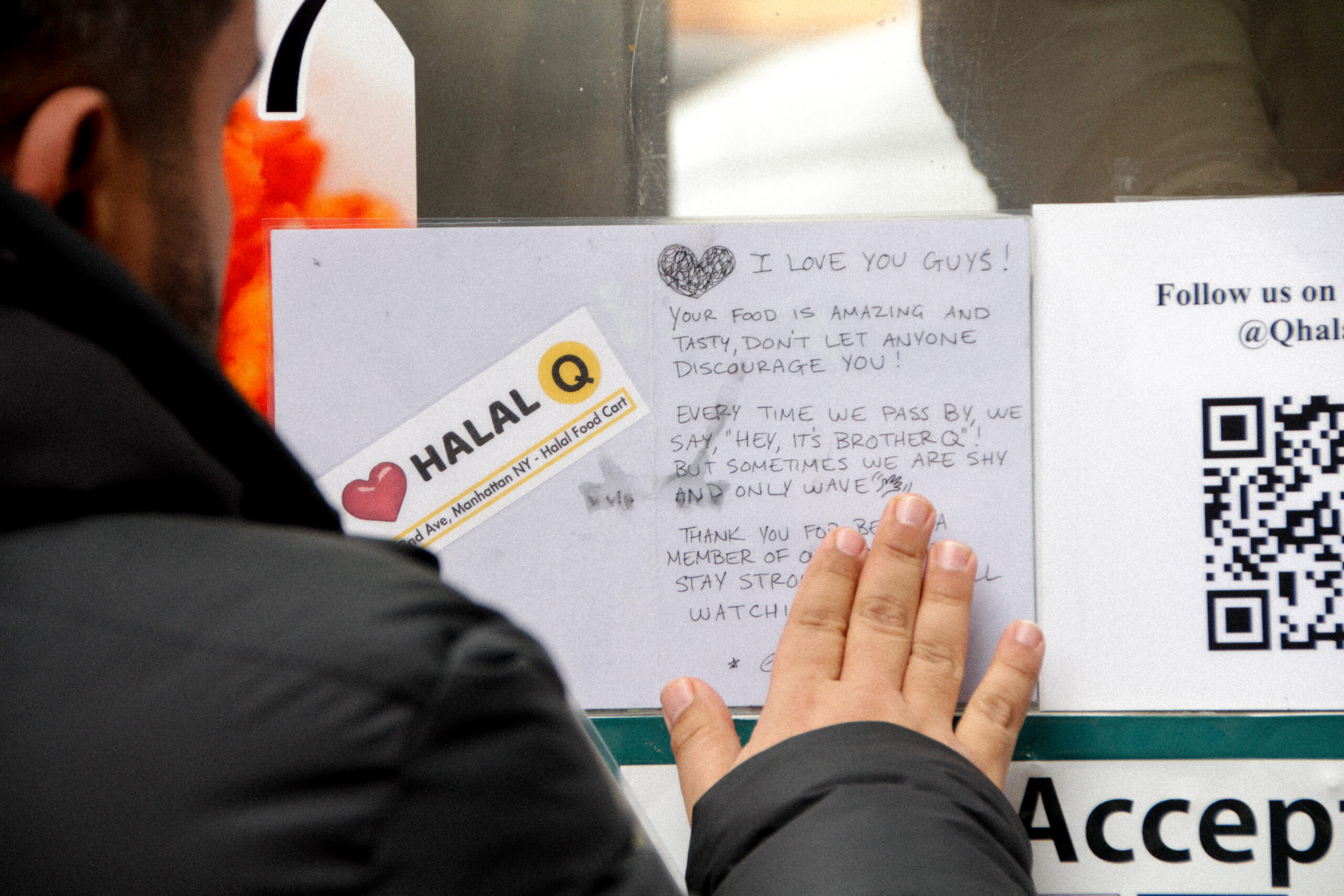

Born and raised in Cairo, Mohsan went to college, earned a degree in architecture, and joined his father in the family real estate and construction business. A friend back in Cairo was the first to tell him about the opportunities that awaited him in the United States. Mohsan won a green card lottery in 2011 and moved to New York, and started his new life working in a halal food cart. A few months later, once he secured an apartment, he brought his family along. Four years later, he had saved up enough to open his own cart at the corner of 83rd and 2nd in Manhattan’s Upper East Side neighborhood. Today, laminated notes decorate the panels of the cart. “Thank you for always being a friendly face!” one of them says. “Your neighbors love you!” says another.

Islam Moustafa, 41, co-owner of Adam Halal Cart, props up a laminated card from a customer on the window of the Halal Cart. “Stay strong,” it says. “We are all watching.” (Credit: Mukta Joshi)

Mohsan is a Muslim. One day not long ago, his halal cart’s Instagram account proclaimed, “Donating food is a key aspect of Islam and feeding the hungry and needy is considered a noble and great deed. Today we are donating food all day for anyone who is in need and cannot afford a meal.” On a recent afternoon, a man wheeled over to his cart and took a soda out of it. “I’m just taking a soda,” he told Mohsan. “Take whatever you want, man,” Mohsan said.

On November 21, Mohsan’s cart made international headlines. Nearly 50 days into Israel’s airstrikes on Gaza, a former advisor for Barack Obama was recorded on video repeatedly harassing Mohsan’s employees with racist and Islamophobic vitriol. “If we killed 4,000 Palestinian kids, you know what? It wasn’t enough,” the man said on the video.

“Whenever someone wants to pick a fight with you, my religion teaches me not to react. Because Allah is watching everything.” That’s why he told his employee, Mohammed, to stay calm. “If he says anything, just tell him you don’t speak English,” he said.

The experience was frightening. But the next day, the former advisor, Stuart Seldowitz, was arrested by New York City Police Department officers, who investigated the incident as a hate crime and charged him. Mohsan and his employees felt safer.

In one of the videos that went viral, a bystander was seen coming up to Seldowitz and telling him to stop. “You’re harassing him,” the man said. “So what if I am?” Seldowitz retorted. After the arrest, Seldowitz was chased by reporters with questions as he was taken away in handcuffs. But in front of the television cameras, he had nothing to say.

On January 17, the hate crime charges against Seldowitz were dropped. As long as he attended an anti-bias training program for 26 weeks, the charges would be dismissed.

Mohsan is tired. After the incident, he was besieged by media requests. He turned down many of them, including one from a reporter who spoke Arabic. He said that he didn’t want to talk to anybody anymore – he didn’t want any trouble. Mohsan had often dreamed of being featured in a newspaper. But he wanted to be recognized for the long lines outside his cart, or because the food is very good, he says. Not like this.

“But I talk to you,” he said. “I feel happy. Because you are a sister.”

Mohsan, 41, is a hard worker. He started working at the age of 18. Today, his business is open seven days a week. He commutes to and from Queens and starts his shift at 7a.m. Mohsan follows the rules. In 13 years, he said that has never received as much as a ticket. He doesn’t let anyone inside the cart. That would be a health code violation.

Mohsan is also very popular. Ever since the video of Seldowitz went viral on social media, New Yorkers have continued to line up outside his cart, ordering chicken and rice, to support him. One customer has come all the way from California. Another, from Amsterdam. The cart’s new Instagram account has nearly 10,000 followers, and a GoFundMe to cover its workers’ lost wages had raised nearly 90% of its goal amount within seven days.

“We are raising funds to support the Adam Halal Food Cart workers who have been targeted by anti-Muslim hate speech and violence. These hard-working individuals are the backbone of our communities, providing delicious and affordable food to New Yorkers from all walks of life,” the fundraiser description says. “In recent weeks, Halal Cart workers have been subjected to a disturbing surge in anti-Muslim abuse and violence. This includes verbal assaults and even threats of deportation and torture. These incidents have left the Halal Cart community feeling scared, vulnerable, and unprotected.”

In 2016, Mohsan and his entire family at the time – his wife and three daughters – were naturalized. “The big one is 16 years,” he says, proudly. “The twins are 12.” His youngest daughter, now 7, was born here. He loves his community and takes pride in caring for it. “I want to feed people,” he said. Selling halal food is what people from Egypt mostly do here, just like Indians mostly work in engineering, he said. Mohsan’s goal is to build a bigger business with three halal carts, maybe four. One day, maybe a restaurant. He wants to employ people who need help and are looking for work in this country. Someone did it for him, and he very much wants to pass it forward.

America is the country of everyone’s dreams, he says.

About the author(s)

Mukta Joshi is an India-qualified lawyer and a fellow at the Toni Stabile Center for Investigative Journalism at Columbia Journalism School.