Bomi Ogunlari is one of two athletes of color on the Dartmouth volleyball team. She is majoring in neuroscience on the Pre-Med track, and is also playing for a Division I team, the highest caliber of National Collegiate Athletic Association play. On the surface, she’s the whole package and in most cases she’d be offered a full ride that covers tuition and living expenses. Instead, she’s struggling to finance her Ivy League education.

In recent years, Ivy League Conference executives have taken a series of steps to improve diversity in their athletic programs. However, critics say the conference’s long-standing refusal to award athletic scholarships at the Division I level is slowing down this progress. Julia Abell, a hispanic Texas A&M track and field athlete who was also recruited by Columbia University said the lack of these scholarships and very steep financial costs have a direct effect on diversity within the conference.

“I think those schools that don’t have an athletic scholarship are missing out on that diversity aspect,” Abell said. “If [recruits] can’t afford to go there, then you’re not going to have that diversity of social class or anything like that, which I think is something important for everyone to see.”

There are 350 schools in NCAA’s Division I. Eight are Ivy League schools — Brown, Columbia, Cornell, Dartmouth, Harvard, Penn, Princeton and Yale. Each has at least 30 sports teams on average.

Competitive sports at Ivy League schools began in the 1870s, with all eight officially forming the “Ivy League” conference with the first “Ivy League Agreement” in 1945. The stance of no athletic scholarships was affirmed within the document.

Collegiate athletics began in the Ivy conference through a rowing association. During the year of the Ivy League’s official founding, Black athletes were not yet welcome on all-white campuses as colleges and their respective sports teams weren’t integrated until the 1950s and 1960s, around a decade after the conference’s formation.

While other conferences within Division I undoubtedly have higher success rates and more national championships, such as those among the Power Five, athletes within the Ivys experience the same 15 plus hour days filled with classes, workouts, meetings, practices and games.

Additionally, Ivy League schools are also defeating other schools held to the Division I caliber from larger conferences. To name one instance, during the 2013-14 men’s basketball season, Harvard earned a bid to the NCAA Tournament as a 12-seed. The Crimson went on to upset 5-seed Cincinnati in the first round.

At the time, Cincinnati had 12 people of color on their 14-man roster, compared to Harvard’s 12 out of 20. Each year, Cincinnati — a member of the American Athletic Conference — has been able to offer full and partial athletic scholarships to over 300 men and women, compared to Harvard’s zero.

Harvard senior defensive back Khalil Dawsey is Black and came from a public high school in Michigan. He said student-athletes who are also people of color within the Ivy Conference are held to further responsibilities.

“I want to see more kids of color, getting into Harvard, getting Harvard degrees, because they deserve it, quite honestly,” Dawsey said. “So I definitely feel as though [I have] added responsibility to my communities — just to exemplify what it looks like to be a person of color.”

On the heels of national racial unrest, the Ivy League Conference overhauled its Diversity, Equity and Inclusion standards/initiatives in July, 2020.

“While the Ivy League stands on a storied history, we acknowledge there were unfortunate chapters that did not advance society towards racial equality,” said Ivy League Executive Director Robin Harris in a public statement. “Moving forward, it is our pledge to examine and identify structural changes needed to promote a diverse and inclusive culture in all aspects of our operations.”

With the absence of athletic scholarships, though, it is unclear how the mission to promote a diverse culture will be accomplished.

And yet, the conference still currently retains enough student-athletes to compete at the highest caliber of collegiate athletics despite the apparent lack of diversity on rosters and draw to other athletic conferences, said Ogunlari.

“This has been my dream for as long as I can remember,” Ogunlari, of Nigerian descent, said. “And, just being able to accomplish that and actually doing it at a high level and at a high academic school is really cool for me to accomplish.”

Private Division 2 AAA 2022 State Champion cornerback and incoming Princeton football player Evan Haynie said while his commitment decision was based on a combination of his passion for athletics and academics, he will use his position as a Black athlete to advocate for more inclusion.

“I think that one of my goals would definitely be to advocate for my diversity because I know that a lot of the Ivy Leagues are making strides to become more inclusive,” Haynie said. “But I definitely think there is some change that could be made. I would like to see more People of Color playing in the Ivy League across all sports.”

Ogunlari also serves as the co-president for Dartmouth’s Black Student Athlete Association, which retains around 80 members.

“Being on a team where it’s predominantly white, has just made it hard to make those different connections with people I had back at home because we had those shared experiences,” Ogunlari said.

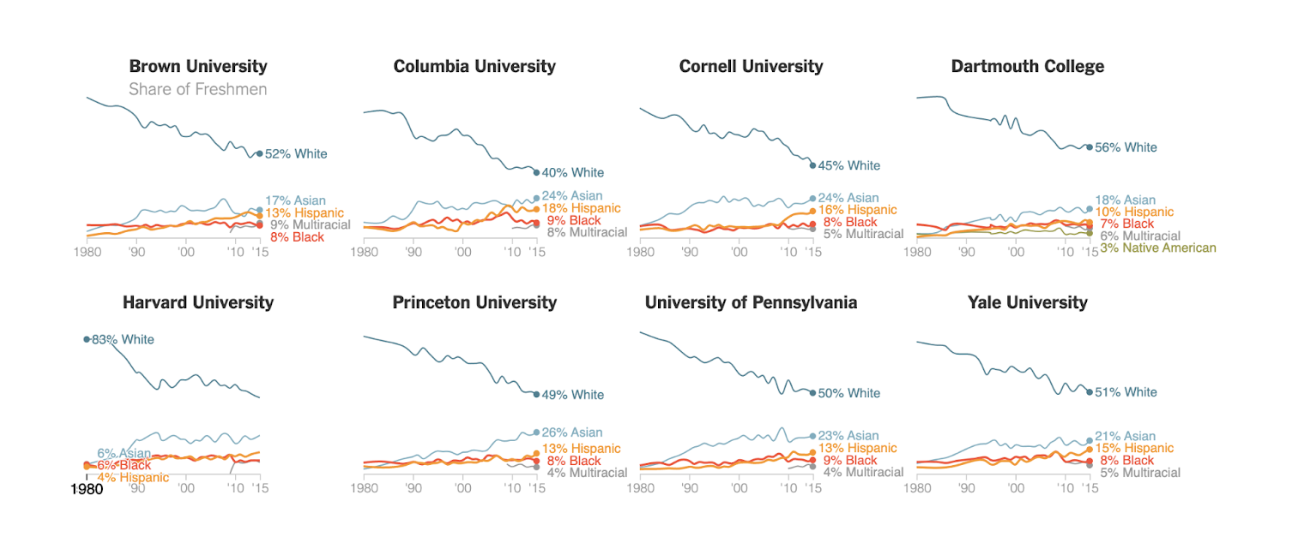

Some current diversity demographics of students within the Ivy League are as follows:

Source: The New York Times

Allie Schachter, who is white, played soccer at Penn during the 2018-2021 seasons. During her time playing for the Quakers, she said she only had four to five teammates that represented minorities out of a primarily white roster.

“The Ivys in general, especially Ivy sports, are not as diverse as they probably should be,” Schachter said. “During the Black Lives Matters Movement, we all wore the same practice warm up shirts, and they said ‘eight against hate.’ They really tried, but it definitely seemed like it was a thing they needed to do, more than them actually kind of believing in it.”

With no athletic scholarships permitted, those athletes who choose to come to the conference are expected to pay for tuition, with the exception of academic scholarships and financial aid.

While financial aid and academic scholarships are available to Ivy athletes, these are resources only granted on a case by case basis. For all students including student-athletes, tuition ranges from $76,932 to $85,967 per year for on-campus students across all eight Ivy institutions, according to the schools’ financial services webpages.

Though, depending on one’s external costs and circumstances, these numbers could be higher or lower.

“Tuition was probably like 100k a year, I would say,” said Schachter. “It was probably down to like, $20,000 [for me with aid.]”

Abell was also recruited by the University of Texas, Oklahoma University in the summer and fall of 2017. Abell chose to attend A&M in part due to a minor athletic scholarship offer.

“At the end of the day, the other three schools were state schools or universities and they could give that athletic scholarship,” Abell said. “I wouldn’t say the lack of an athletic scholarship was definitely the number one reason I didn’t go [to Columbia, however] it was a factor.”

Columbia, Penn and Yale’s financial aid offices all declined to go on record with financial information regarding athletes and the ramifications it has on Diversity, Equity and Inclusion.

The Ivy League also upholds strict limitations pertaining to its eligibility rules, further deterring athletes and thus more diversity to its conference. Within the conference, there is zero redshirting — pause in play resulting in an extension of eligibility — or permission for graduate students to participate in athletics; an athlete must complete their collegiate athletic career within their first four years of enrollment, no pauses permitted.

“The emphasis is too much on like the student, the student, the student,” Ogunlari said. “But athletes here are also working hard to prove their place. Me and my whole team have been against these rules.”

Despite its challenges, the reason athletes flock to the conference is due to the mix of academic achievement while also playing at the Division I level, said Haynie.

“That was really the deciding factor for me,” Haynie said. “To know that I could still fulfill my childhood dream of playing Division I football but also playing at arguably one of the top schools in the country. Knowing that Princeton, not only was getting to play football but also is going to set me up for life after football.”

But, this draw to the conference also places the athletes in an environment lacking diversity paired with strictly enforced rules, causing athletes of color to seek each other out for support.

As of presstime, the Ivy League Conference communications department has not responded to requests for comment.

“If [athletic scholarship rules] were changed, I’d be ecstatic, regardless of whether I’m here or not,” Dawsey said.”

About the author(s)

Jennifer Streeter is currently pursuing a Master of Science at the Columbia Journalism School with an emphasis on sports reporting.