Ava Powchik was having a terrible day. She had just left an emotional doctor’s appointment last December and was crying as she waited on a street corner for an Uber. Soon, a man pulled up in his car. He began shouting sexual comments and invited Powchik into his vehicle.

“My first thought was, ‘Really? Now? You see a young woman crying alone and you think now is a good time to sexualize and harass her?’ ” said Powchik, a 25-year-old casting assistant. “Luckily, this was broad daylight on a busy corner so I felt comfortable declining and walking away.” Powchik said that she regularly gets harassed when she leaves her apartment on Manhattan’s East Side.

Catcalling – the verbal form of street harassment that is a by-product of New York City life for many women – has continued during the pandemic, many victims have reported. Their accounts are somewhat counterintuitive. “I thought that wearing a mask and sunglasses would provide me enough anonymity and camouflage to stop the catcalling, but that hasn’t been the case,” said Powchik. “If anything, those who catcall seem to be more empowered underneath their masks to say whatever they want.”

The continuation of street harassment despite widespread mask-wearing underlines a message that advocates have been putting out for a long time: that catcalling has little to do with the way women present themselves. That’s a point that will be highlighted during International Anti-Street Harassment Week 2021, taking place April 11-17. The weeklong series of events aims to raise awareness of the ongoing prevalence of catcalling through social media advocacy.

“Street harassment has never been about what women look like,” said Holly Kearl, founder of the nonprofit Stop Street Harassment. “Street harassment is the manifestation of the inequalities that exist in our country, be that sexism, racism or homophobia.”

Little data on catcalling before or during the pandemic is available, but Sophie Sandberg, founder of Catcalls of NYC, said that many women have told her they feel more unsafe outside during the pandemic. This is partly because perpetrators often “break social distancing guidelines and get within six feet, or even take off their masks when catcalling,” she said.

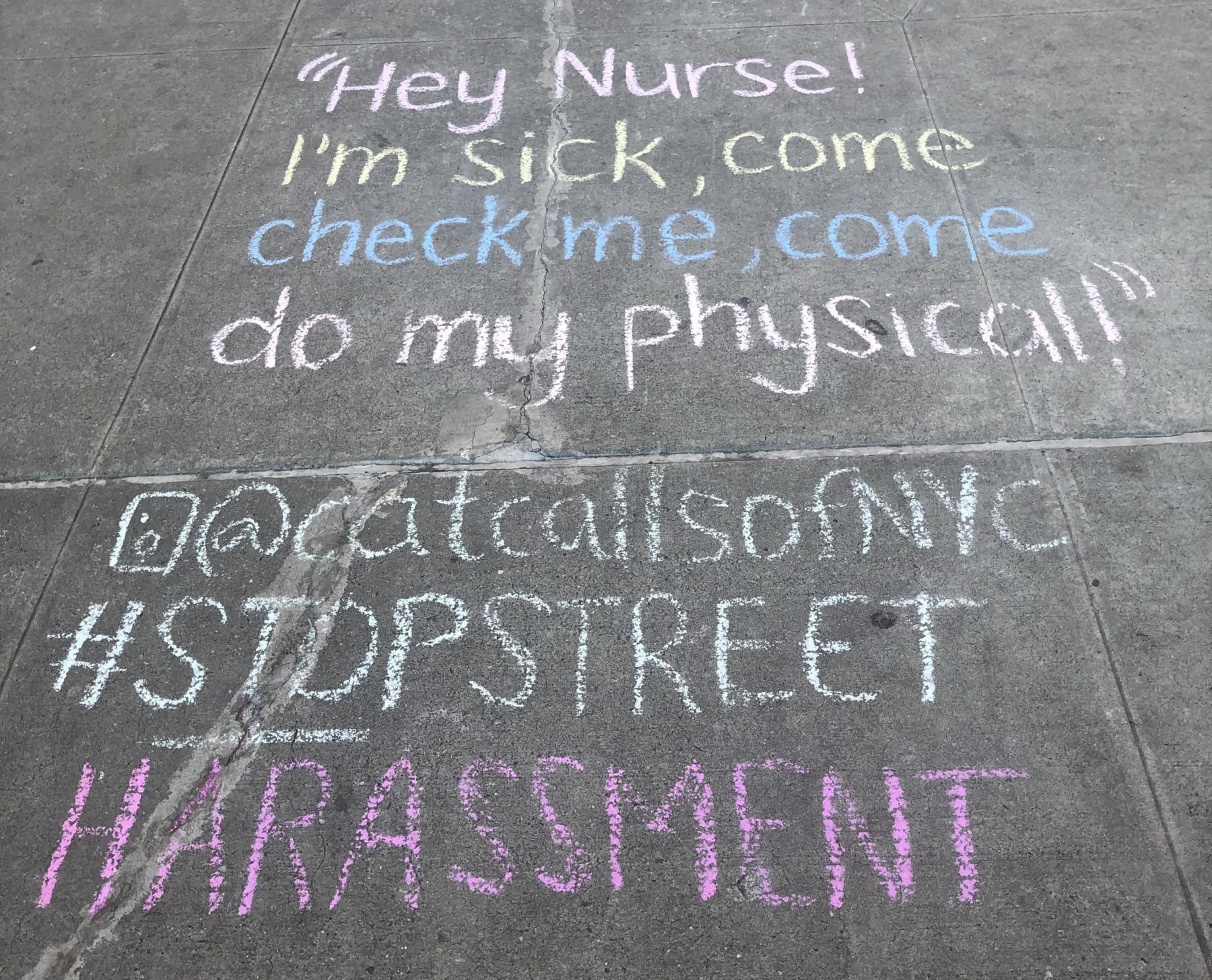

Sandberg founded Catcalls in 2016 with the aim of making the ubiquity of street harassment more visible. The group solicits online submissions of “real” catcalls from victims, and volunteers then write out the statements, in striking multicolor chalk, on New York sidewalks at or near the locations of the original incidents.

Their work has not slowed down during the pandemic as the Covid Catcalls reel on their Instagram site suggests. “The anonymity of the masks makes catcallers bolder,” Sandberg said. “There are also inappropriate comments that have been made towards women wearing masks that are hyper-sexualizing.”

Like Powchik, Jonida Konjufca – a 17-year-old high school junior and resident of Manhattan’s Upper East Side – has recently experienced harassment from perpetrators in vehicles. While walking six blocks to the gym in February, Konjufca said men in a truck made “kissing noises” and shouted criticism about the way she was dressed. When she ignored them, they cursed at her. “I was very scared they were going to harm me for ignoring them because I could sense they were getting angry,” Konjufca said.

Christi Steyn, a 25-year-old content creator who lives in Soho, said she often feels too scared to say anything back to harassers. “I don’t know what can happen if I stand up for myself. I don’t know if it’s going to provoke anyone,” she said. “You feel violated and uncomfortable.”

Steyn turned to spoken word poetry to voice her frustration over street harassment and posted a recording of a piece on TikTok in December. “This feeling / Dirt / You make me feel dirty,” reads Steyn. “Do you have a sister? / Or a mother? / Do you want her to feel this way?” The video has now received over 55,000 views.

Marissa O, a 26-year-old actress and singer/songwriter living in Hell’s Kitchen, recalled a recent incident that occurred as she was on her way to work at around 9 a.m. She was wearing a face mask, a hat and a long puffer coat, none of which stopped a stranger from harassing her.

“He commented on how beautiful I was,” said Marissa, who felt her safety would be compromised by giving her last name. “I was a human sleeping bag, so I’m not sure what he was referring to as beautiful when I was wrapped in goose feathers and waterproof fabric.”

Kearl of Stop Street Harassment is calling for more education, starting “as young as possible,” on the importance of respecting women. Anti-Street Harassment week features many such events, including virtual workshops, sharing experiences online and online trainings on how to intervene to stop harassment.

“The reality is, until we have equality in our society – and in our interpersonal relationships – we won’t see equality in public spaces,” said Kearl. “Street harassment will continue as long as women and girls are devalued.”

About the author(s)

Ella Creamer is currently based in Manhattan as a graduate student at Columbia Journalism School. Her reporting interests include international politics and economics, health and gender issues. She is also interested in how data can help us better tell stories. She grew up in the U.K. and studied at the London School of Economics before moving to the U.S. You can reach her by email: ellalouisecreamer@gmail.com or on Twitter: @ellacreamer2.