The hospital building at Ellis Island on Nov. 16. Some immigrants were placed here for temporary holds or before being sent home. (Credit: Eleanor Hildebrandt)

When Cornell University hired Thomas Hoebbel to make an immigration documentary, the filmmaker knew his own family’s history would help in his research. He remembered the stories his mother and aunts told him about his ancestors from Ireland.

“She spoke Irish and English, my great grandmother, and brought her habits and idiosyncrasies with her,” Hoebbel said. “She sprinkled the grandkids with holy water during thunderstorms and that’s something we don’t do anymore. When I went to Ireland and we were staying with a friend and we left to travel back to Dublin, her mom got out the holy water and gave us each a little splash for our safe travels.”

Hoebbel’s great grandmother was one of the 12 million immigrants who arrived at Ellis Island, the first and largest federal immigration processing center that served as an entry point from 1892 until 1954. After the passage of the Immigration Act of 1891, which gave the U.S. government authority to regulate who entered the country, the port became a symbol of the American dream.

Immigration issues factored heavily into the 2024 election and continue to dominate the first executive orders of Pres. Donald Trump’s second administration. But as immigration becomes a focal point of American politics and continues to divide voters, some Ellis Island descendants are turning to their personal histories to inform their political opinions and family values.

“My family came here 100 years ago and it’s because we were welcoming to immigrants that we are able to be here,” said Hoebbel.

“Now, to get into this country, it takes months or years and the amount of hoops people have to jump through just to get on American soil is so egregious. Yet, all of our ancestors only had to pay the fare and get on the ship.”

Vincent Cannato, author of “American Passage: The History of Ellis Island,” and history professor at the University of Massachusetts Boston, is also a descendant of Ellis Island immigrants. His grandfather came from Italy in 1909.

He said Americans were divided over who and how many people were let into the port the same way they are concerned about U.S. borders right now.

“The issue of immigration that we have in our country today — the controversies, the political debates — this is nothing new,” he said. “So many of the debates we have today are debates that were held 100, 150 years ago. They’re strikingly similar.”

A decade before Ellis Island opened, the Chinese Exclusion Act was passed, marking the first time the U.S. government forbade an ethnic group from entering the country. While the act was initially supposed to last 10 years, it stayed enacted under the Immigration Act of 1924 until the Immigration Act of 1965. Additionally, “lunatics” and “idiots” were barred from immigrating alongside criminals before Ellis Island opened.

Yet a common theme is pride in one’s immigrant ancestry.

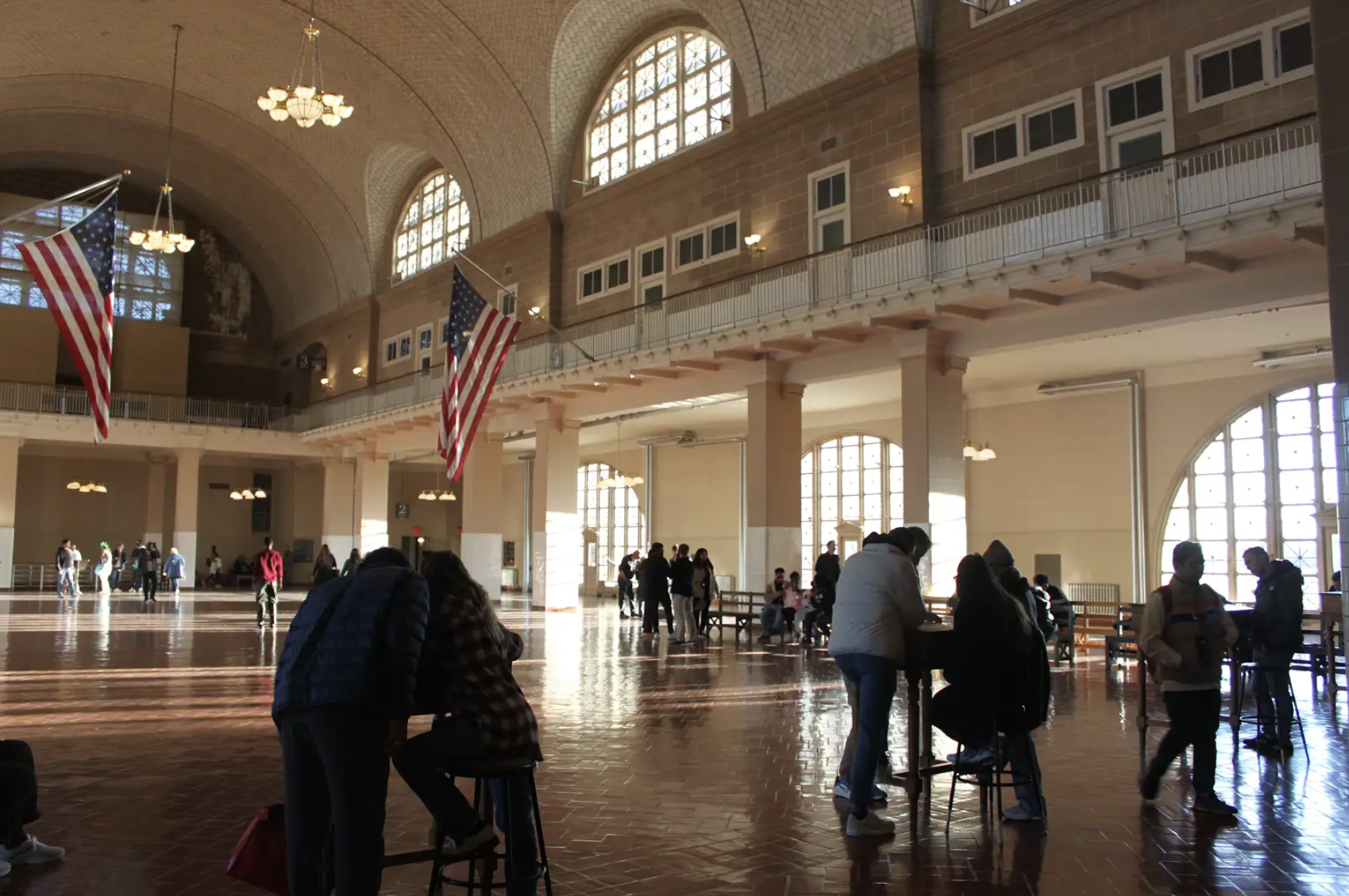

The Ellis Island Museum entrance on Nov. 16. Most immigrants who went through the port waited here to be processed. (Credit: Eleanor Hildebrandt)

Denise Giachetta-Ryan, a semi-retired nurse in Staten Island, volunteers a few days a month at the Ellis Island National Museum of Immigration.

“I love doing these tours because I just feel like I belong here,” she said.

Three of Giachetta-Ryan’s grandparents immigrated from Italy through the port before 1920, she said. They found homes in Manhattan’s Little Italy — where she grew up. She said her familial connection helps people open up on her tours and speak about their personal or familial immigration stories.

Since 2000, between 1.8 and 4.5 million people have visited this museum annually, except during the pandemic.

Cannato said Ellis Island reminds people of a “golden time” in migration and is a symbol of the country’s melting pot history. Only 2% of immigrants were turned away at the port, according to the Ellis Island Foundation, after a doctor diagnosed them with a contagious disease or a legal inspector was concerned about a public charge or an illegal contract laborer.

In general, most immigrants at this time were of a lower socioeconomic class and predominantly from southern, central and eastern Europe.

The Registry Room is where many Ellis Island immigrants would wait for inspections and registration. The process usually took less than a day. (Credit: Eleanor Hildebrandt)

Upon arrival, immigrants were inspected on sight.

“If you have four to 5,000 people coming every day, each person doesn’t get their own medical exam,” said Cannato. Instead, doctors and inspectors would closely look at immigrants to check for illnesses, disabilities or other issues. The process, from inspection to the proof of identity, lasted two or three hours, he added.

Giachetta-Ryan carries a buttonhook on her lanyard to show visitors the tool used to check for trachoma, a chronic and highly contagious eye infection during the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Cannato said Ellis Island remains one of the most prominent and central symbols of migration in the U.S., and its connotation is positive in most American’s minds.

The symbolism is part of the reason one New York statewide immigration organization chose the name it did.

The Ellis Island Initiative, a coalition of New York advocacy groups, was founded in 2023 and helps integrate migrants into various communities around the state. Rovika Rajkishun, who was a formerly undocumented immigrant from Guyana, is now the partnerships strategist for the group and said the organization’s name reminds people of a time when the U.S. had a different take on immigration.

“We wanted a name that evokes a time when we welcomed immigrants, when we thought of immigrants as a positive,” she said. “The story is more nuanced than that, but we also wanted to show folks that our country benefited from migration through Ellis Island.”

Giachetta-Ryan believes her liberal views on immigration were mostly shaped by her teenage years in the more politically and socially open society of the 1960s. She said her teenage years were filled with acceptance, something that actively impacted her political views.

Giachetta-Ryan wants to share her understanding of immigration with her family and is making sure her great nephews and nieces know the country’s history.

“They’re very interested,” she said. “I’ve bought them coloring and children’s books from here because it’s important that everybody knows that this is where they came from. I still think it’s amazing my grandmother came at 15 or 16, my grandfather at 16, all by themselves. Imagine having that fortitude to get yourself over here. The kids need to know that.”

About the author(s)

Eleanor Hildebrandt, originally from Iowa, is a Stabile investigative fellow at Columbia Journalism School. She was a Fulbright Scholar and has previous bylines in Iowa Capital Dispatch and PolitiFact.