LaGuardia Airport Terminal B is shown (Credit: Laura Kukkonen)

New York’s LaGuardia airport has already bagged second place in the list of airports most at risk from sea level rise. But things could be much worse.

Last year, a widely-reported study stated that New York City is sinking. A more recent study has shown that parts of the city are sinking and rising at different rates. According to NASA, this can increase local flood risk linked to sea level rise. This makes LaGuardia even more vulnerable than previously believed. Its rate of subsidence – the technical term for sinking – is more than double the average rate for the city.

The study that came out in late September 2023, was led by a team of researchers from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California and Rutgers University in New Jersey. It says the city-wide sinking is as a result of a process known as Glacial Iso-static Adjustment (GIA). During the Ice Age, parts of New York state were buried under a heavy sheet of ice that weighed its land down. New York City was on the perimeter of this ice sheet, causing the land here to be pushed up. It is now readjusting downwards.

The fastest sinking areas, such as LaGuardia and Arthur Ashe Stadium highlighted by the study, are built on landfills. LaGuardia’s construction required landfill to be brought from the nearby Rikers Island and laid onto a metal framework. Landfills are vulnerable for two main reasons. First, their local topographic elevation is likely to be lower; that is, they are already close to sea level. Second, the ground beneath them tends to be less stable.

Despite investments into flood resiliency during the latest renovation of LaGuardia, the heavy rainfall in late September 2023, flooded the airport, forcing flight cancellations and making people wade through the waters. But it also faces a quietly creeping risk of getting covered in water much sooner than even some current reports say.

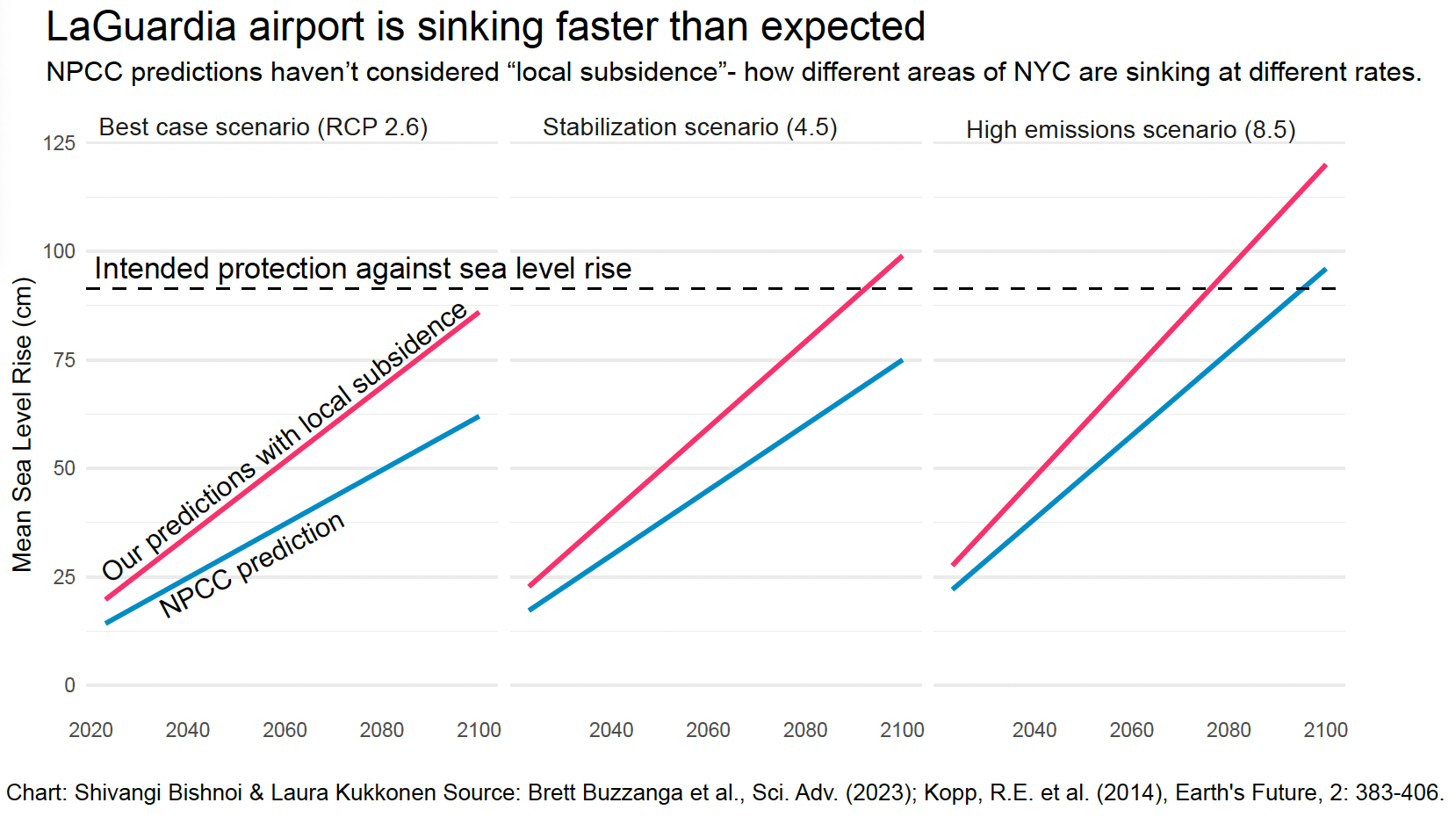

Previous estimates of mean sea level rise from the New York Panel on Climate Change (NPCC) suggest that the airport would be underwater by 2100 and will start facing monthly flooding from high tides by 2050. But this does not account for the much faster rate of local sinking.

We wanted to understand how the new study and faster sinking rates would affect these projections.

We wanted to understand how the new study and faster sinking rates would affect these projections.

Local sea level rise is affected by a few different geological factors, with subsidence (sinking) being one of them. The current estimates from the NPCC assume a uniform rate of sinking for the entire city based on the tide gauge at Battery Park. For our projections, we bumped it up to levels expected from the new study.

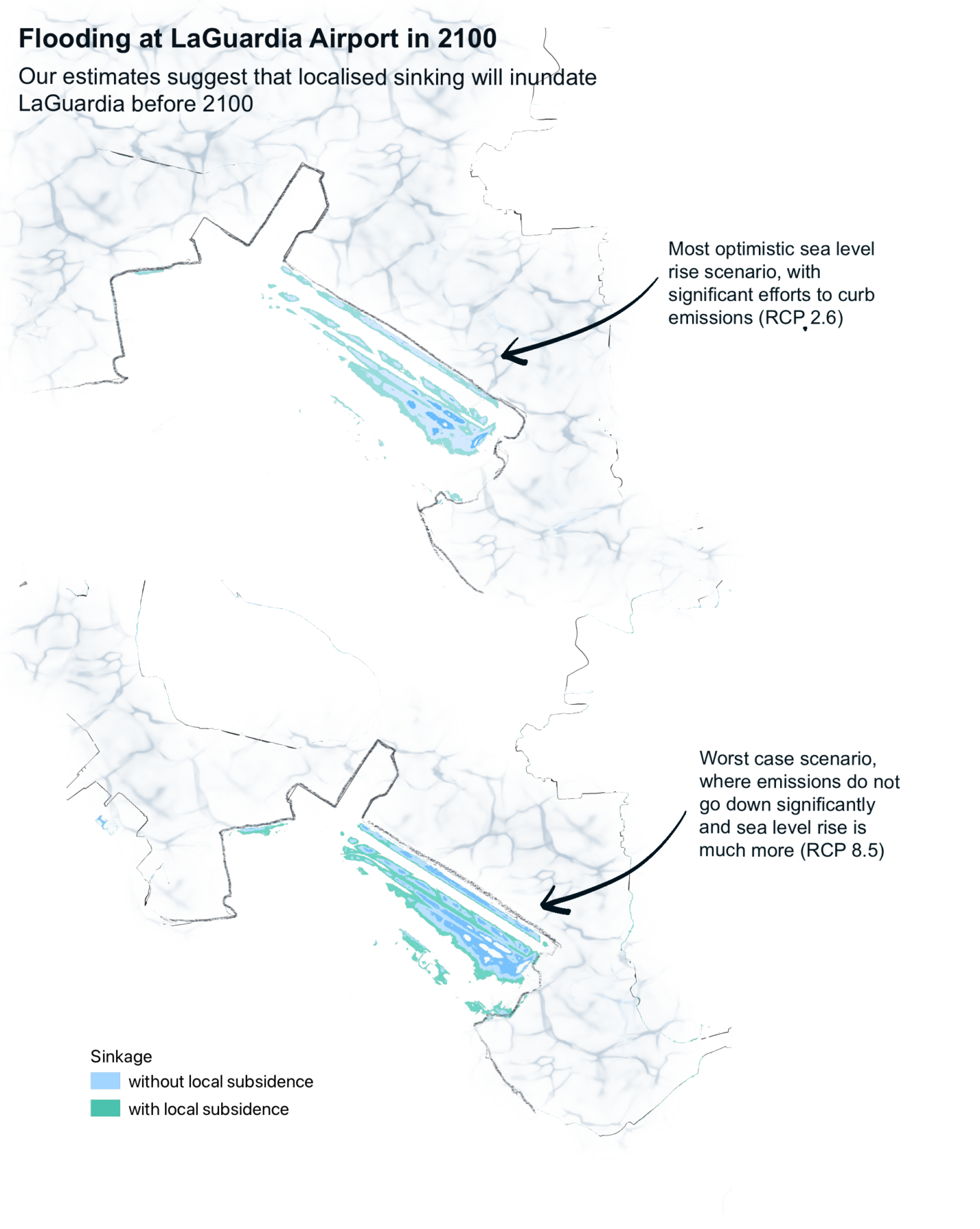

Our calculations suggest that even in the most benign climate scenario, where efforts to curb climate change are the most significant – so called RCP 2.6 – the sea level rise is being underestimated by roughly 38 percent. This means that the airport could start going under water sooner than expected.

Robert Kopp,a climate and sea-level scientist and a climate policy scholar at Rutgers University has co-authored the new NASA study and also the NPCC report from 2019.

“I would assume that the engineers at LaGuardia were well aware of subsidence before it was observed from space. That an airport built on fill would be sinking faster than surrounding bedrock should not be a surprise to anyone. But I do not know how that has factored into Port Authority planning, either before or after our study,” he said by email in response to our calculations.

The challenges from storms will probably be felt even sooner. Earlier reports have suggested that Sandy was not the worst case scenario for LaGuardia. And if the storm had hit during the high tide, water could have reached up to 12 feet above sea level, drowning not just runways but large parts of the airport.

LaGuardia’s vulnerability is emblematic but not unique. The sinking problem at Arthur Ashe Stadium, a tennis complex at Flushing Meadows–Corona Park in Queens, has been known for a while. The new roof that the stadium got in 2013 was made of fabric because the building could not afford to put any more weight on soil that was already giving way. Another fast sinking spot is Governor’s Island, which ironically, is set to host a $700 million Climate Campus.

Comparing elevation data to data from the NASA study shows that many low lying areas are also sinking faster than the rest of the city. The study highlights the fact that planning for the long term is not optional anymore because it may be sooner than we think.

The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) told Thomson Reuters in a 2020 report that they plan to mitigate risks but not those projected as far into the future as 2100.

“The FAA cannot reasonably evaluate impacts 80 years and beyond,” the source had said in a statement to Reuters.

LaGuardia has undergone major renovations in recent years. The upgrades’ estimated cost is around $8 billion in total. The project was completed in 2022, after Terminal B’s renovations and opening of the new Terminal C.

Port Authority’s CEO Rick Cotton told NBC that resiliency was a major chunk of the airport’s 8 billion renovation. LaGuardia has introduced ways of protection against tidal flooding and storm surges: in addition to large water pump stations, an earthen berm and steel wall around the airport, Terminal B has flood proof walls, flood doors and deployable flood shields.

According to the Port Authority’s Climate Resilience Guidelines published in 2015, the agency is supposed to protect its critical assets against a so-called 100-year storm – which means a storm that has the probability of happening on average only once every 100 years – plus up to three feet of potential future sea level rise. The Port Authority’s press release from 2022 says that in project designs they add an additional two-foot safety factor to the three feet rule.

A safeguard of three feet, under our revised estimates, still suggests substantial risk under the most ambitious scenario to curtail emissions. It increases to a roughly 50% risk of flooding by 2100 if curtailment efforts are less successful. The risks from high tides and storms also could be higher and likely to hit sooner.

So far the efforts have had ups and downs.

In 2021, the airport was all over the headlines after storm Ida hit because it didn’t flood. But in September 2023, during heavy rain and local flooding in the city, the airport’s Terminal A building flooded and was forced to close. Hundreds of flights were grounded in all the three major airports in the city.

The Port Authority declined to comment on LaGuardia’s situation.

Taking a wider view of the city, Vivien Gornitz, climate scientist and a member of the New York City Panel on Climate Change (NPCC) says that New York City is actively working on the challenges that floods and sea level rise might bring.

But she adds that their timeline, too, is shorter.

“Their planning tends to be for the 2050s, for the not-that-distant future,” Gornitz says.

Do scientists believe that what New York is doing is sufficient to ensure a sustainable future?

“It could still not be enough, depending on how the future trend line is going to evolve, which is up in the air,” Gornitz said.

Gornitz and her colleagues at the NPCC have made projections further in the future, even showing scenarios where extreme weather becomes more common and accounting for the low probability but high impact scenarios of the Antarctica Rapid Ice Sheet Melts (ARIM). NPCC’s task is to inform city policymakers about these scenarios. It is in the process of writing a new report. Vivien Gornitz says that while the new study will take into account local and regional effects, it is unlikely to do so at neighborhood level as in the new study.

The question of whether investing billions of dollars in a fast-sinking area is wise is a multi-pronged one. On the one hand, flood resiliency is more important here than elsewhere.

“I think not having new construction in an area that’s low lying is definitely one important component,” says Jacqueline Austermann, an Assistant Professor at Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory.

“That’s an easy one to say,” Austermann said. “We should definitely not do that.”

On the other hand, regarding LaGuardia’s situation, she says that securing an area like an airport could be more simply done than a densely populated residential area, where people, their homes and quality of life could suffer from the floods or protective measures, like large structures or even relocation.

About the author(s)

Shivangi Bishnoi is an economist turned data journalist. She is a current M.S. Data Journalism student at Columbia Journalism School and covers climate, economics and public policy.

Laura Kukkonen is a Finnish journalist and data journalism student at Columbia Journalism School.