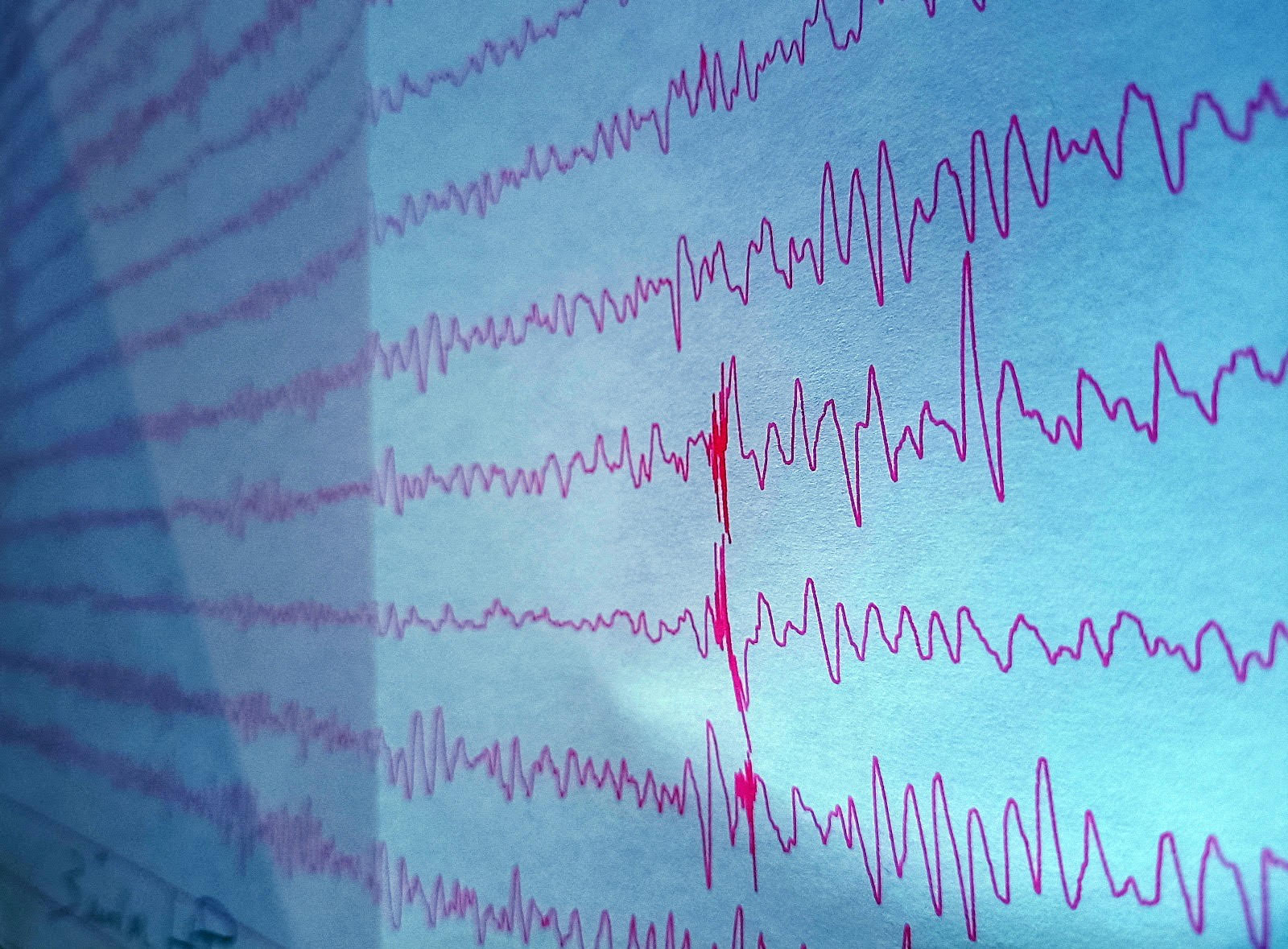

Electroencephalograms, a test that measures electrical activity in the brain, are shown. (Credit: Giulia Leo)

Elizabeth Roldan’s alarm goes off at 7:45 every morning in her studio apartment in Harlem. By 8, she has swallowed 500 milligrams of Lamictal and another 300 of Keppra.

Roldan has been on these anticonvulsants since Christmas day, 2003, when she had her first tonic-clonic (grand mal) seizure at age 21. One moment she was sitting at the dining table celebrating with her family in New Jersey, the next she was in the hospital, receiving a diagnosis of epilepsy.

“It was just a perfect storm of triggers,” Roldan said, referencing a cluster of stressors that hit at once. “I remember the night of Christmas Eve, I went to the club in New York, slept for 3 hours, and drove to my family immediately after. I also had a horrible first semester in grad school and, when I came home, I just wanted to drop out.”

At the time, Roldan was also dealing with the stress of her then-fiancé and now-ex-husband, Rafael Rodriguez, completing his first deployment in Afghanistan.

Jaqueline French, a professor at NYU Langone’s Comprehensive Epilepsy Center, defined epilepsy as “a brain state” that causes frequent seizures. In some cases of focal epilepsy – when doctors can identify a hyper-excitable area of the brain that is responsible for the seizures – the disease can be cured through surgery. However, in cases of generalized epilepsy, anticonvulsants are often the only known way to reduce seizures.

Roldan is now 41 and has been dealing with generalized epilepsy for the past two decades. Every morning, she makes hard boiled eggs in the air fryer. She only uses the stove occasionally, but just the back burners, so that if she has a seizure, she doesn’t risk the pot and its boiling hot contents falling onto her.

Twice a week, she leaves home at 11 a.m. and takes the subway to the gym. While she waits for the train, she stands far back on the platform, away from the edge for fear of having a seizure and falling onto the track.

“When it comes to transportation, it’s better to live with epilepsy in New York City than anywhere else,” French said. “In many states, you can’t drive for six months to a year after you’ve had a seizure, and if you live on a farm in Kansas, you need to drive to get to the closest pharmacy. But a lot of people in New York can walk to their pharmacy. Some of them have to take public transportation, but at least there is public transportation.”

However, New York’s transportation system isn’t always reliable, which contributed to one of Roldan’s worst seizures. Back in 2018, she found herself out of anticonvulsants on the night that a blizzard was forecast to hit New York. Afraid of getting stranded in the storm, Roldan decided to pick up her drugs first thing in the morning. That meant skipping her evening dose, but she didn’t think that would be a big deal.

She spent the night at her grandmother’s house, which was not near a subway stop, and when she woke up the next morning, the bus wasn’t running because of the snow. She was stuck at her grandmother’s all day, unable to get anywhere. By the time Roldan managed to get on the road it was 6 p.m., and she had skipped two doses of medication. As she walked the short distance between the bus stop and the pharmacy, she collapsed to the ground with a seizure. A stranger down the street saw her and came to her aid.

“New Yorkers are nice,” said Roldan. “This guy was like, ‘I don’t want to leave you, but I have to go to work,’ so he gave me his phone number to call if I needed anything. I have him saved as ‘nice seizure man.’”

Until January, Roldan would spend her afternoons, as well as part of her mornings, working at the Huntington Free Library in the Bronx. She was able to get a research assistant position after the library received a private grant. But now the library has run out of funds to pay her, and Roldan is looking for a new job.

In the meantime, she keeps herself busy by writing a screenplay for a fictional series inspired by her life as a single woman with epilepsy living in New York City. She has spent two years working on “Single and Seized” – that’s the working title of the show – but she has yet to finish the screenplay because of several memory and attention problems related to her epilepsy.

At 8 p.m., Roldan swallows 500 mg of Lamictal and another 300 of Keppra, regardless of where she is and whether she has water with her; she has mastered the art of collecting saliva in her mouth to take the pills without water.

If she goes out at night, she makes sure to leave once the clock strikes 10. A regular sleeping schedule, she discovered, is as essential as drugs to keep the seizures at bay.

“You know you’re not partying until three or four in the morning with Elizabeth,” said Rafael Rodriguez, who divorced Roldan in 2016 after the two grew apart. “She’s pretty much like Cinderella in that way.”

Once she’s home and in bed, Roldan sets her alarm for 7:45 a.m.

About the author(s)

Giulia Leo, originally from Bari, Italy, is a reporter and audio producer at the Columbia Journalism School.