Shushianna Kidd poses with her child (Credit: Isak Hüllert.)

Parents at a playground near the corner of Frederick Douglass Boulevard and West 142nd Street in Harlem are typically anxious, watching their children from the park benches no more than 10 feet away. But, asked about keeping their children safe from a severe illness like polio, however, they can have different responses.

Shushianna Kidd, 23, a hospital employee and biology student at City College of New York, decided not to vaccinate her four-year-old son against polio, for instance. “Home remedies are fine for me. I use honey, lemon, ginger, and other natural things. We don’t know what they put in the vaccines,” Kidd said.

Attitudes about polio vaccination have taken on new urgency after a Rockland County man was diagnosed with paralytic polio in July, the first polio diagnosis in the United States in nearly a decade. Subsequent wastewater testing by the State Department of Health detected 70 “positive samples of concern” related to poliovirus in five New York counties, including New York City, as of October 7.

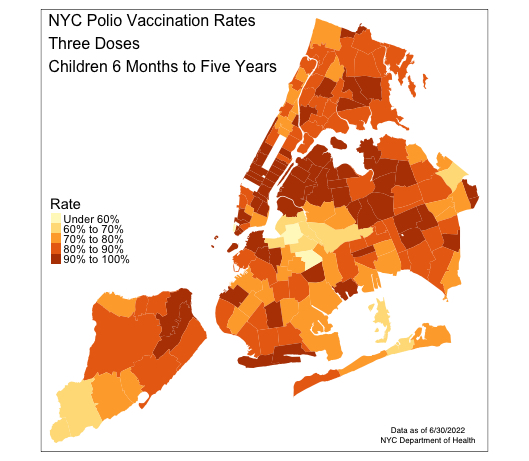

In all five zip codes in Central Harlem, fewer than 80% of children ages 6 months to 5 years old have received the recommended three doses of the polio vaccine as of June 30. One zip code in particular, 10030, has the second lowest rate in all of Manhattan, at 72%, according to city health department data. Those rates are well below Manhattan’s (92%) and New York City’s (86%).

Credit: Jake Indursky

Vincent Racaniello, a microbiologist and immunologist at Columbia University Medical Center, said that “72% is too low.”

“That concerns me because it’s not high enough to prevent cases of polio. So, I would not be surprised if we see them at some point in the future, and in Harlem specifically.” He said that 90% of a population should be vaccinated to attain herd immunity and halt disease spread.

New York Gov. Kathy Hochul declared a state of emergency as a result of circulating poliovirus in early September. While the state requires children who attend day care and pre-kindergarten through 12th grade at public, private or religious schools to be vaccinated against poliovirus, those requirements can be circumvented through a medical exemption, which is a form signed by a licensed physician explaining why a student cannot receive one of the vaccines required for enrollment. According to Racaniello, it’s “relatively easy to get exemptions to such vaccine requirements.”

On a recent Sunday afternoon, Yvonne Santos, 67, watched her grandson from a park bench in Marcus Garvey Park in Harlem. She was shocked to hear about vaccine hesitancy in her neighborhood. Polio presented a very real danger to Santos, who grew up in the 1960s and ‘70s; she described a friend growing up with one leg shorter than the other because of polio.

“The vaccines are a blessing,” Santos said.

From a medical perspective, the solution seems simple, Racaniello said.

“We have a great vaccine that works really well. It’s cheap, easy to give, very few side effects – and the virus doesn’t change,” Racaniello said. “As long as you can get people to be vaccinated, that’s the key.”

But, he and other experts have acknowledged that in low-income or minority communities, vaccination is no simple matter.

“The biggest problem that you see about vaccinations isn’t vaccines, as much as who it is that wants you to get vaccinated,” said Robert Fullilove, a public health expert and associate dean for community and minority affairs at Columbia University Medical Center.

Fullilove pointed out that Harlem residents harbor suspicions toward city and state governments that “have not done anything to help” with housing shortages or homelessness, making some residents reluctant to take government advice about health. “It’s not about polio, and it’s not about the vaccine,” Fullilove said. “It’s about, ‘Somebody I don’t know is going to stick a needle in my arm.’”

In Central Harlem, which is 54% Black, community disinvestment coupled with historical medical racism may explain much of the resistance to vaccines and other health care interventions.

“Historically, Black people have been mistreated in terms of health care,” said Racaniello, citing “the notorious Tuskegee experiment” – in which Black men with syphilis went untreated even after the discovery of a cure – which African American families “still remember to this day.”

Kidd, whose child remains unvaccinated, was wary of what is in vaccines.

“They should break down every detail about the vaccines and their side effects,” said Kidd. “But that is never going to happen because there is stuff in them. They are not open about it.”

Andrew Avella, 37, said he believes his youngest son, Andrew Jr., 3, developed autism from childhood vaccinations. “Why are we forced to take vaccines? I don’t know what they are adding, and I don’t trust the CDC,” he said, pointing to the Tuskegee experiment as an historical analogy.

Attitudes in places characterized by a historic lack of healthcare access may reflect “an ongoing suspicion and ongoing resentment that ‘government is the last set of individuals to try and convince us that what they’re about and what they’re doing is in our best interest,’” Fullilove explained. “Because their lived experience is ‘Nah, not really.’”

Jennifer Erickson, 40, who has vaccinated her children against polio, acknowledged the lack of trust in Harlem, but had less patience for vaccine hesitancy.

“I believe in science. I trust science,” Erickson said. “All those people who are out here doing their own research — where’s your lab? Where’s your beaker? If they want to call me a sheep, then ‘baah.’”

Some parents, like Stephanie Lopez, 29, have not decided whether to vaccinate all their children yet. Lopez, whose three-year-old son received the polio vaccine, was deliberating what to do for her six-year-old son. She asked her primary care provider for information. “I asked about the side effects and told him I was iffy about putting stuff in my children’s body,” she said outside P.S. 092, located on West 134th Street in Harlem.

Rose Santos, 35, an educational director at Drew Hamilton Early Education Center in Harlem, has seen the effects of vaccine hesitancy at her program. “Some are even hesitant about seasonal flu vaccines,” she said. “They feel like they are putting stuff in their child’s body.”

Santos pointed to less knowledge about vaccines and medical information in African American populations. “It would be nice if they had people come in from the community and educate” communities where hearsay and rumors circulate.

Kidd agreed that an information void in the community led residents to take medical matters into their own hands. “Without information about the vaccine and its side effects, people will make up their own information. They become hood doctors,” she says.

The City Health Department has not responded to several requests for comment on outreach being done around polio, but they have included on their website reminders of ways that residents can be vaccinated.

Racaniello, an expert immunologist, was skeptical about top-down vaccination efforts’ efficacy in improving vaccination rates in historically vaccine-resistant communities, including Hasidic Jewish enclaves like those in Rockland County, which sits just 30 miles north of Harlem. Rockland County, which has a history of vaccine hesitancy, was where the initial paralytic polio case involving a young Hasidic Jewish man occurred. According to Racaniello, the state health department set up free polio clinics and administered roughly 400 new vaccinations, “which is not enough to make a difference in that community.”

The State Department of Health said on its website that the documented case and wastewater results underscore “the urgency of every adult and child, particularly those where poliovirus has been identified, getting immunized and staying up to date with their polio immunization schedule.”

Racaniello suspected that such efforts in Harlem would yield “a similar low uptake,” and instead would require patient-by-patient outreach from healthcare providers or religious leaders.

“You have to overcome long-standing problems they have with trusting medicine, and I don’t think that’s easy to do just by setting up a vaccine station,” Racaniello said. “This is a tough problem, and it needs to be addressed.”

About the author(s)

Isak Hüllert, a native of Denmark, is a student at Columbia Journalism School hoping to specialize in political reporting and long-form writing.