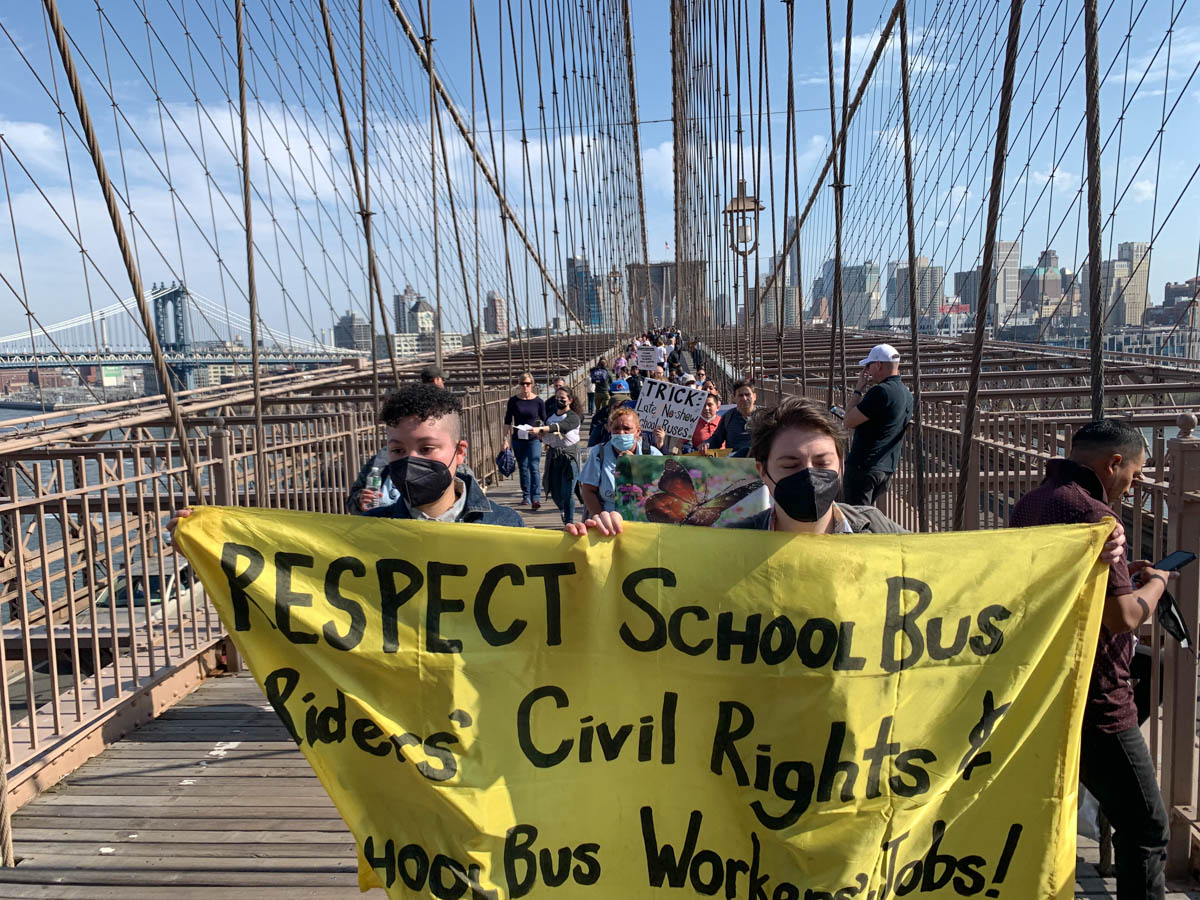

On March 19, Lucas Healy, a 13-year-old on the autism spectrum, led a march of advocates across the Brooklyn Bridge who chanted, “Transit equity for all.” Lucas is a student at District 75, a New York City program that supports children with special needs in education.

Paullette Healy, Lucas’ mother, described how often the school bus doesn’t show up – or is late – to pick up her son, among other issues. “My child was left at the wrong building,” she said, providing one example.

The shortage of bus drivers in New York City and nationally, and its ripple effects, has worsened amid Covid-19 and school closures. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, New York State’s bus drivers dropped from 18,600 in May 2019 to 15,480 in May 2020, a decline of about 17% after only two months into the pandemic.

This decline has particularly affected children with disabilities. For this reason, groups like Parents to Improve School Transportation (PIST), Amalgamated Transit Union local 1181-1061, and Bronx Autism Family Support, are pushing for a citywide referendum in November to vote on the School Bus Bill of Rights. If passed, it would address the myriad busing-related issues that have compromised students’ health and their ability to learn. This bill would also pave the way to better and more accessible communication between parents and the Office of Pupil Transportation (OPT) within the Department of Education, which is currently lacking, according to the advocates and parents.

Disruptions, such as arriving late to school, reduces class time and worsens students’ learning, said Gloria Brandman, a retired New York City public school teacher who worked with students with special needs and who attended the march. “If they come to school late and they’ve been on a bus an excessive amount of time, their energy level is affected, their attention span isn’t strong,” Brandman said. “And we’re talking about children that already have some difficulties with attention, with physical impairments, emotional issues.”

Giselle Ramirez, the mother of a child with special needs, who also attended the march, has experienced just this. “My son’s regression has been very visible. He was from being able to count to 100 to now not even being able to count to 20 because he gets to school tired,” said Ramirez. During the first two weeks of this school year, her son had to miss several classes because no bus arrived, and Ramirez often had to pay for an Uber ride or go to work late to drive him to school.

Even when buses show up, they have often been short-staffed, without a matron or paraprofessional to support children with special needs.

Brandman gave the example of a teen on the spectrum who would often bang his head. At times, he could not take the bus because no paraprofessional was available to support him.

”For the 26,000 students in District 75 and all other students with disabilities that require transportation, it is a related service under the law, not a privilege,” said Amy Tsai, a mother of a teen with disabilities and a member of the Community Council for District 75, where the majority of students ride a bus to and from school. “Families are in desperate need of a change.”

In January, the U.S. Department of Education announced a joint temporary action with the U.S. Department of Transportation to help address the school bus drivers shortage. With this action, the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration (FMCSA) is giving states the option to make testing for commercial driver’s licenses (CDL) easier. This measure became effective on January 3, 2022, and will expire on March 31, 2022.

New York Gov. Kathy Hochul has also moved on this matter. In September 2021, she directed local agencies to expand CDL training opportunities and, in January 2022, announced a proposal to enable third parties to conduct commercial driver license road tests.

However, according to Sara Catalinotto, founder of PIST and organizer of Saturday’s march across the Brooklyn Bridge, multiple factors need to be considered to solve the problem.

Each bus, for example, is assigned to children from different schools and does not have a fixed route. This is particularly distressing for children with disabilities, who need routine and consistency.

In addition, bringing students together from different schools leads to issues like bullying. “If someone is aggressive to somebody else on that bus, if they were all from the same school, the principal could bring the parents,” Catalinotto said.

Then, there’s the legislative aspect. In 2013, former New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg removed the Employee Protection Provision (EPP), a protection for school bus workers that retained their seniority rights, wages, and benefits when hired by different bus companies. This has made the work of school bus drivers less desirable and thus contributed to the decrease in public demand for this job.

“If you make the job less stable, less attractive, you will have turnover. People will quit,” said Catalinotto. “And the children won’t have that stability and won’t have that experience and institutional knowledge.”

PIST drafted the “School Bus Bill of Rights” to address these issues, as well as better and more accessible communication between parents and the Office of Public Transportation (OPT) within the Department of Education. Now, they are pushing for a referendum in November to vote on the School Bus Bill of Rights at the city level.

“When we’re talking about school transportation, we want that transportation to be reliable and safe. We want the workers to have the workers’ rights that they need, the salaries that they need for the job security that they need, and that ensures the benefit of the children who are going to be taking their transportation,” Jo Anne Simon, state Assembly Member for the 52nd District and a former disability civil rights lawyer, said at the march.

As the march moved across the Brooklyn Bridge to the Department of Education, Lucas asked, “If we can’t get to school safely, how can we learn?”

About the author(s)

Eleonora Francica is a journalist from Rome, Italy, and holds a bachelor in international affairs with a minor in philosophy.