Nazir Popal woke up fearing for his life for more than eight years. As an Afghan interpreter for U.S.-led forces, he was twice nearly kidnapped by the Taliban and saw dozens of colleagues murdered. Now he serves fried chicken in East Harlem.

“I didn’t know life was going to be so difficult here,” said Popal, peering from behind the cracked plexiglass at Crown Fried Chicken. “I don’t care if I have to sleep in the subway or on the street, but I have a wife and three kids.”

Earning just $9 an hour, he is currently two months behind on rent. His shifts are punctuated with desperate calls to state agencies as he tries to obtain emergency funding to avoid losing his home. Last month, he found out his food stamps and cash assistance had also been cut off. Already exhausted, he has now been forced to pick up gruelling 18 hour shifts to scrape together what little money he can.

After waiting six years for his application to be processed, Popal came to the country last year under the Special Immigrant Visa (SIV) program, set up in 2009 to allow at-risk Afghans who worked alongside U.S. forces to resettle here. Now he’s considering moving back.

“I had this idea of what America would be like, but it was all a lie,” said Popal. “I spend every day worrying about what is going to happen next.”

Popal is not alone. More than 16,000 Afghan SIV holders have resettled in the U.S. since 2014, a figure set to increase by upwards of 50% following the mass-evacuation from Kabul in August, according to the International Rescue Committee. With only three months of federal resettlement assistance, they are forced to find whatever work they can before this economic lifeline runs out. As a result, even before the current wave, roughly 6,000 Afghans with college degrees had already been forced into low-wage jobs, according to the Migration Policy Institute, an immigration think tank.

“We call it ‘brain waste,’” said Jina Krause-Vilmar, the CEO of Upwardly Global, a nonprofit that helps refugees rebuild their careers in the U.S.

According to Krause-Vilmar, around three quarters of Afghan SIV holders who come through their doors have at least a bachelor’s degree, yet 35% are underemployed and a further 65% are unemployed entirely. “They feel like it’s another death,” she added.

It is a problem repeated up and down the country. Afghans who risked their lives aiding U.S. forces during the nation’s longest war say they have been left to fend for themselves. Many are stuck in dead-end jobs struggling to make ends meet. Others are unable to find work at all.

After arriving in the U.S., Popal moved into a distant uncle’s basement apartment in Queens, where he shared a windowless 3 by 4 meter room with his wife and three children. When his uncle offered him work at his fried chicken shop across town, an industry which Afghan-Americans in New York City have held a corner on since the 1970s, Popal decided to take the job. He just wanted to find a home of his own, he said.

Popal once dreamt of setting up a business of his own, but these ambitions seem all but impossible two years on. There are no savings. No rainy day fund. His goals are reduced instead to what most take for granted — whether that’s finally being able to buy a table for his family to eat on, or replacing his children’s run-down school clothes.

“I was always there for this country when they needed me,” said Popal. “But when I need help now, why is nobody there for me?”

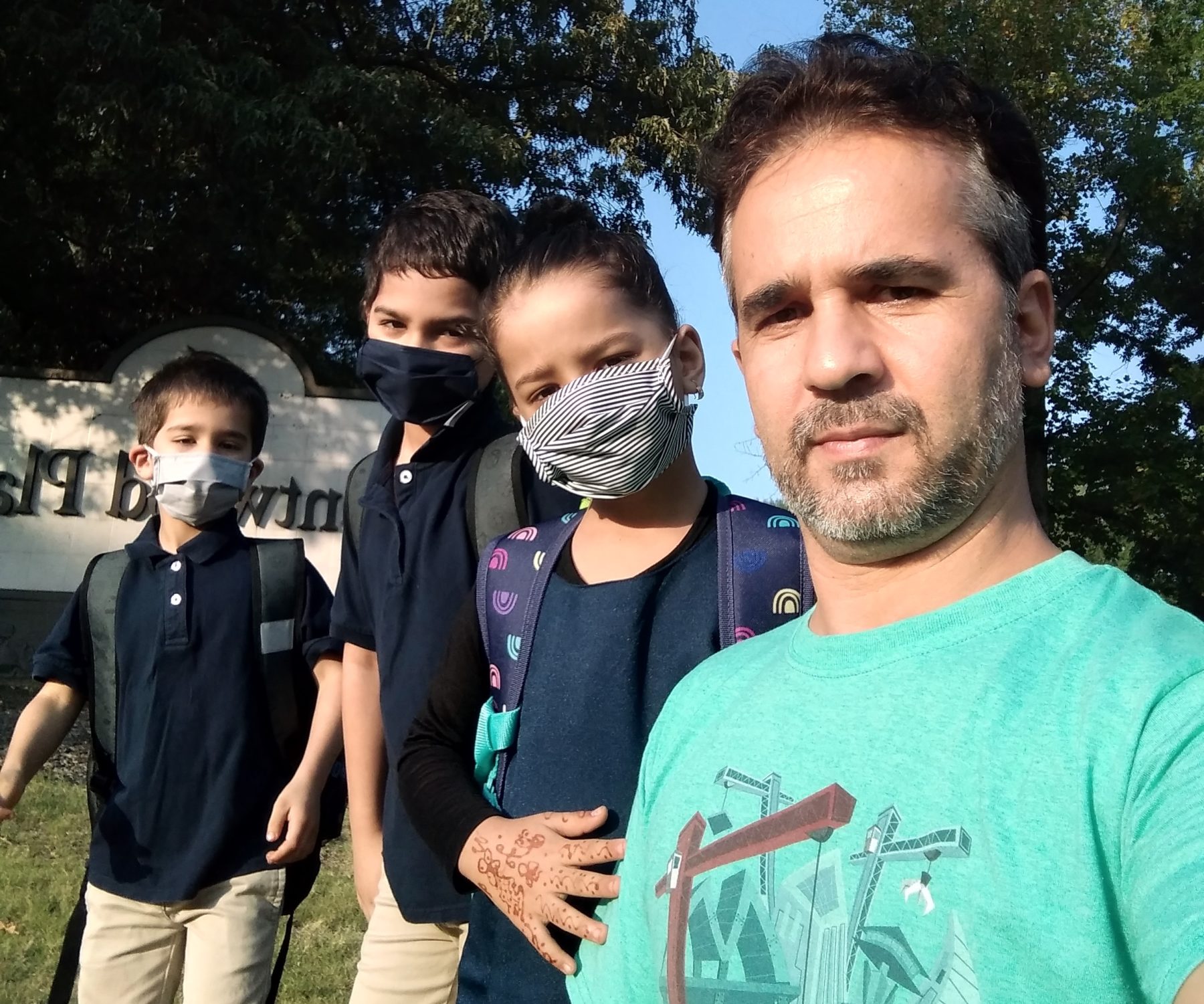

Across the country in Memphis, Noor Habib and his wife Seeta are former Afghan journalists who fled the country in October of last year after a string of Taliban death threats. They worked for media outlets operated by U.S.-led forces for more than ten years, and Noor frequently risked his life doubling as a frontline interpreter. Now, they are struggling to provide for their four children.

“When we first arrived, we were applying for so many different positions but nothing happened,” said Seeta. “It was just so difficult.”

Out of options, and with the end of federal resettlement assistance looming come January, college-educated Noor was forced to take the first job he could: working the night shift in an Amazon warehouse for $15 an hour.

During his 12-hour shifts, Noor must process more than 400 packages per hour. His productivity is tracked constantly by a computer monitor in front of him, along with any time he strays off task, whether that’s going to the bathroom or bending down to pray at his station.

“You have to complete your count,” said Noor. “If you don’t, they terminate you.”

Although Seeta later found work in the county government, she does not qualify for medical coverage because it’s a temporary position. In fact, just 25% of Afghan SIV holders reported working in jobs that provide health care, according to No One Left Behind, a non-profit that supports them in the U.S with financial aid and employment assistance.

Habib and his family, already struggling to make ends meet, are now expecting their fifth child and fear being crippled by looming bills.

Following the mass-evacuation from Kabul in August, the approximately 65,000 Afghans now being resettled in the U.S. have until just December before their funding runs dry. Then, they’ll face the same reality. Most have been evacuated under humanitarian parole, which allows them to enter without visas. It is believed, however, that “at least” 40% of parolees aided the U.S. military and thus qualify for SIVs that couldn’t be processed in time, said a spokesperson in a Department of Homeland Security statement.

Although Afghans evacuated under humanitarian parole were recently granted additional benefits such as Medicaid and rental assistance under a long-awaited $6.3 billion emergency funding bill, they are still not afforded permanent legal status. According to resettlement agencies, this leaves them even less employable – companies simply not willing to invest in individuals whose presence has an expiration date.

As he drearily closes the shop shutters to go home for the night, Popal pauses to reflect on what lies ahead for his fellow countrymen. “I don’t want to see anyone else going through what I am,” he said.

About the author(s)

Euan Ward is a former Beirut-based journalist specializing in conflict, corruption, and human rights abuses. He has covered stories for outlets including The Guardian, CNN, and Al-Jazeera.