Revered for its modern, elegant design of precisely placed steel, the George Washington Bridge soars above the Hudson River, connecting Manhattan to Fort Lee, New Jersey. At night, its lights twinkle like the diamond necklace worn by Cassie Louise Lightfoot in Faith Ringgold’s book Tar Beach.

“Form follows function,” said George Deodatis, a professor of civil engineering at Columbia University. “Nothing is superfluous, and the construction is meticulous.”

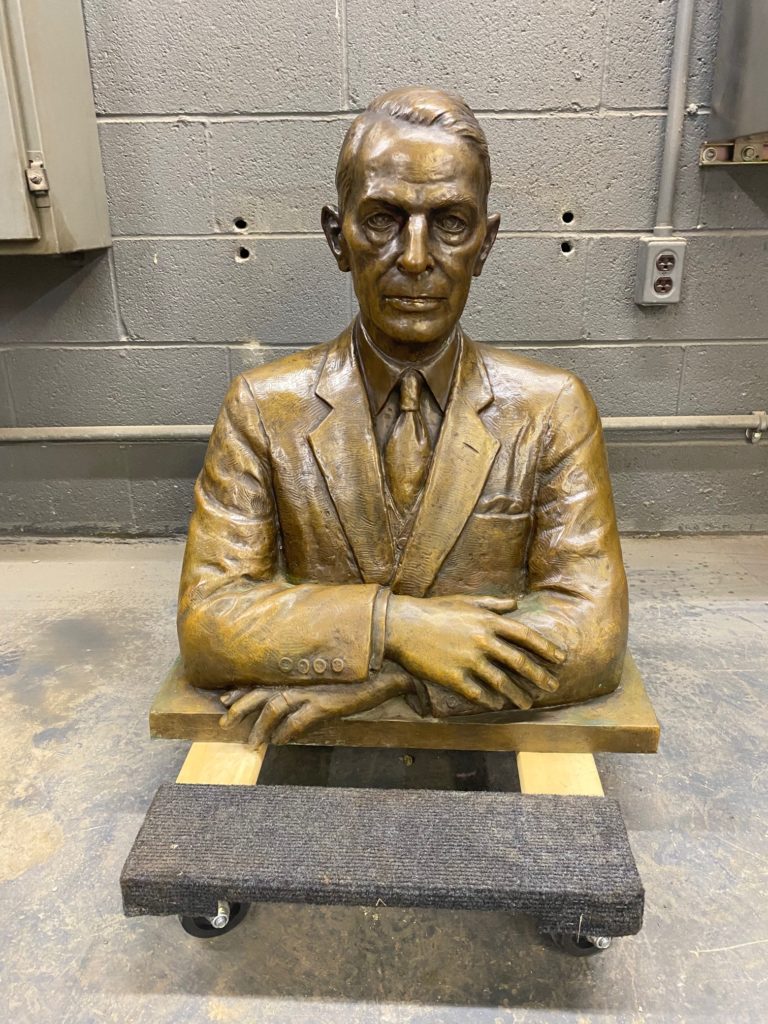

Millions have walked, bicycled and driven over the bridge since its opening in 1931, but few people can name the man who devised it, Othmar H. Ammann. A bust of him had sat in the George Washington Bridge and Bus Station in Washington Heights, but it and a bust of George Washington were removed in 2013, when station renovations began.

The station’s general manager, Kenneth Sagrestano said hiring an architect to design and build pedestals for the artworks – a total cost of $20,000 to $40,000 – is not in his budget this year due to decreased revenue related to the coronavirus pandemic. But he hopes to have both busts back on display by the bridge’s 90th anniversary next year, on Oct. 25.

“The statue is a testament to Ammann and the bridges he built,” said Sagrestano, who often climbs the bridge with his workers. “The statue represents the marvel of engineering and his contributions to the region and all of his bridges.”

Many people who use the terminal look forward to Ammann’s return.

For Lizette Mercado, 54, who commutes from her home in Englewood, New Jersey, to her job in Manhattan’s Garment District, the view of the bridge and Hudson River are priceless. “I don’t know who built it, but I love coming over the bridge. If there’s a statue, bring it back,” she said.

“People want to know the story of the bridge,” said Marva Buchanan, a 54-year-old healthcare provider who travels by bus from Newark to New York City every Monday. “He shows that immigrants count.”

Ammann was 25 when he arrived in New York from Switzerland in 1904. He found work almost immediately as a civil engineer in a city that was expanding upward and outward.

To win the George Washington Bridge job, he competed with his boss, Gustav Lindenthal, who built the Queensboro Bridge and others.

Lindenthal’s design spanned the Hudson River from 57th Street to Hoboken, New Jersey, and emphasized rail travel, at a cost of $200 million. The more practical Ammann advocated for the upper Manhattan site for $75 million, convincing governors that his plans were the most aesthetic and that cars were the future of travel. In 1962, a few years before his death, Ammann added a lower deck to the bridge for a total of 14 traffic lanes.

Construction began in 1927 on Ammann’s bridge, which he called his daughter. The bridge opened on Oct. 25, 1931, as the world’s longest suspension bridge, and under budget at $59 million, in part by eliminating ornamental stonework that revealed its steel foundation.

“This modern steel bridge integrated New York City into a regional transit system and helped fuel the departure of people from New York City after World War II,” said Robert W. Snyder, Manhattan Borough historian.

After the George Washington Bridge was completed, Ammann designed the Robert F. Kennedy (formerly known as the Triborough), Verrazano-Narrows, Bronx-Whitestone, Bayonne, Whitestone, Throgs Neck and Ward Island bridges.

Ammann’s bust was placed when the bus station opened in 1963, following the completion of the bridge’s lower level. No information on the sculptor is available, Sagrestano said.

The monument rested on a black marble pedestal on the terminal’s main floor. Ammann faced the bridge, his arms folded, while the bust of George Washington sat diagonally across from him near New Jersey Transit bus ticketing counters.

Ammann watched commuters rush to work, pigeons battle for crumbs, and bettors yell at OTB screens for their horse to win, place, or show. Homeless men and women lived in stalls in cavernous restrooms where signs reminded travelers not to wash anything but their hands in stainless steel sinks.

Cloaked in weary sepia tones of ancient nicotine and age, the station had not been renovated since it opened. When the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey began work in 2013, the busts were placed in a secure electrical room on the New Jersey side of the river.

Ammann’s grandson, Larry Ammann, recalled from his home in Charleston, Virginia, that Ammann was a perfectionist who rode a golf cart around his massive offices filled with drafting tables.

Even a telephone call from television host Ed Sullivan inviting him on his show did not deter him from his passion. His wife relayed the request to her husband, said Larry Ammann, 79.

His reply: “‘Tell him, “Thank you but not interested.” Who’s Ed Sullivan?’”

Othmar H. Ammann’s renown for resourcefulness extended to the end of his own life at age 86 in 1965.

“Grandfather requested to be cremated,” Larry Ammann said. “He found it expedient, and it saved money.”

Ammann’s ashes were sprinkled onto the Hudson River so they would flow below his bridges.

About the author(s)

Arlene Schulman is a journalist based in New York City. Her work is focused on documentary filmmaking at Columbia Journalism School.