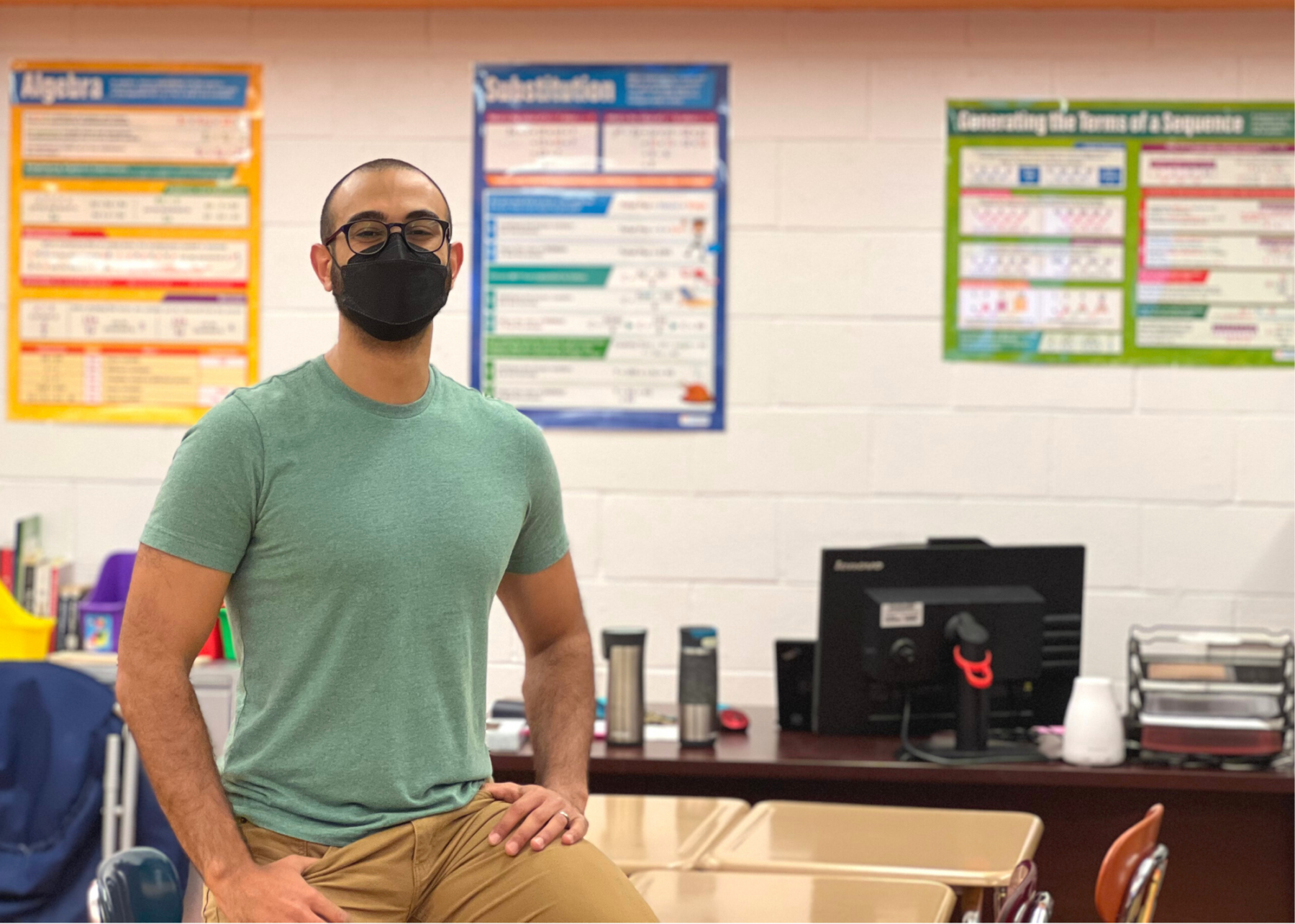

After months of remote learning, Mohammad Jehad Ahmad entered his classroom for the first time last March and stumbled upon a small white device.

Ahmad, a high school math teacher in the Bronx, soon realized the device was an air purifier, but he didn’t know how to use it. “It was unplugged in the center of the room,” said Ahmad. “I imagined whoever put it there, put it there for a reason, but there was no extension cord or anything to plug into.”

He remembers other teachers saying that the purifiers should stay in the middle of the room for best efficiency, but no one was really sure because they didn’t receive any guidance from their school or the city’s Department of Education (DOE).

Since the beginning of the pandemic in March of 2020, educators have been discussing the need for air purifiers to improve air quality and fight COVID-19 in schools. This need is particularly evident in classrooms that rely solely on windows for ventilation, as is the case for thousands of New York City classrooms including Ahmad’s.

It was around springtime, and the weather was getting warmer. For the rest of the school year, Ahmad didn’t use the purifier, relying instead on his classroom windows for ventilation.

Over the summer, he came across news stories and social media posts criticizing the purifiers, but he didn’t pay much attention until the first day of school in September, when he encountered not one but two air purifiers in his classroom. This prompted him to do his own research.

“I wanted to make sure it wasn’t just people complaining for the sake of complaining,” said Ahmad. “What I learned was that these purifiers were not as effective as they should be for the price.”

The DOE purchased two air purifiers for each city classroom, priced at $549 each, for a total of over $40 million. The model they chose is the Intellipure Compact, and the DOE’s purchase was the largest in the company’s history. Chicago Public Schools, City University of New York and Cornell University are among other educational institutions that have purchased the same purifier.

In August, students from Townsend Harris High School in Queens broke the story that the air purifiers are not “HEPA purifiers,” as claimed by the DOE.

HEPA stands for High Efficiency Particulate Air. “It’s a standard for how many particles and what size particles the filter captures,” explained Faye McNeill, a chemical engineer and professor at Columbia University. The HEPA standard is set by the U.S. Department of Energy and has gone through peer-reviewed testing since the early 1940s.

“Nothing works as efficiently and as cheaply as a HEPA filter does,” said Alex Huffman, an aerosol scientist at the University of Denver. “They’re rated to take up 99.97% of the particles that are hardest to filter.”

While HEPA is a standard experts recommend, there is no official certification for commercial air purifiers. No governmental agency is vetting the products before they hit the market.

Intellipure states that “every unit is individually tested and certified to guarantee better than HEPA efficiency.” In a statement to CNS, Christian Cobb of Intellipure’s parent company HealthWay said that, “the Intellipure Compact has been independently tested by LMS Technologies, Inc. and many others.”

The only available data on the LMS Technologies, Inc. test relies on the percentage of efficiency. The Clean Air Delivery Rate (CADR) is unavailable. Huffman said that, “What matters is the efficiency times flow rate, which is why these tests are usually rated in CADR. Efficiency alone is almost worthless information.”

He suggests looking into testing of the Compact conducted by the Built Environment Research Group at the Illinois Institute of Technology. They tested the product’s CADR for four particle sizes, and the data shows low efficiency.

When questioned about their choice, a DOE spokesperson told CNS that “The units we chose use a technology that filters to .007 microns, which is beyond the HEPA standard of .3 microns.”

“That’s a misnomer,” said Jake Jacobs, a middle-school art teacher in the Bronx. “Anybody could walk down the street and say something is better than something else. It’s not accurate. Just describe your product.”

The purifiers have four settings: low, medium, high and turbo. Intellipure says that the Compact is “ultra-quiet.” Some teachers disagree.

“Turbo sounds like an airplane. If I had them both on turbo, I wouldn’t be able to hear the kids at all,” said Sarah Allen, a first grade teacher in Brooklyn. “The kids have gotten really good at speaking loudly. And we’re used to really projecting so they can hear us better.”

Jacobs has been frustrated by how loud the purifiers are. He sets the fan speed at medium, which he said is quiet enough. “The only question is: how much filtering is it doing? I have no idea,” he said.

Kimberly Prather, an aerosol scientist at the University of California, San Diego, said “the lower settings don’t filter the air as fast. But it’s better using the lower settings than not using them at all.”

For the purifiers to be effective, it’s vital to ensure proper placement, setting and frequency. Placing them by open windows, for instance, would filter mostly fresh air, rather than what’s circulating in the classroom.

This is a lesson Ahmad learned the hard way. One of his classroom walls is full of windows. Initially, he placed one of the purifiers by that wall and the other one on the opposite side of the room. “None of this was based on fact,” he said. “I just thought one would clean one side of the room and the other would clean the other side.”

“You don’t want it to be in a corner,” said McNeill. “You want it to be in an area where the airflow isn’t obstructed.”

Another important tip is to leave the purifiers on during recess. “Make sure they don’t turn it off when the people leave the room,” said Huffman. “It basically flushes the air out while they’re gone. People may have the idea of energy savings. But that’s just not what we should do.”

When asked whether the DOE provided instruction or guidance to city teachers, a spokesperson told CNS that “if educators have questions about how to use their air purifiers, they should connect with the custodial engineer for support,” who “are experts on their buildings and ventilation systems.”

Ahmad’s high school did not respond to a request for comment.

“I’m lucky that in my school, our custodians got some guidance from their supervisor,” said Allen. The custodians turn the purifiers on and off at the beginning and end of the school day, so teachers don’t have to.

Though Ahmad, Jacobs and Allen have done their own research on how to use the purifiers, that’s not the case for all teachers.

Allen said the lack of guidance made it so that some teachers don’t use them at all. “I heard one teacher saying it’s a doorstop, they use it to hold the door open. Some set their coffee on it. Others are still in the closet and have never been opened.”

The novelty of the purifiers has also confused some students. “Some days the air purifiers get turned off because a kid thinks it’s an air conditioner,” said Ahmad. “I have to double check them after every period.”

At first, Jacobs’ students would trip or bump into the purifiers. “The whole front cover would fall off,” he said. “It happened again and again.”

Students at Stuyvesant High School in lower Manhattan have had mixed experiences.

“I didn’t even notice them,” said Hana Glanz, a junior.

Lea Esipov, also a junior, said she tripped over one of them on her way to her desk. “They’re a little loud,” she added. “Masks already make it hard to hear, but it’s no big deal if it keeps us safe.”

Experts encourage teachers to use the purifiers to educate their students. “Explain what the filter does and try to remove the mystery of this virus,” said Prather. “Teach students and get them to have a sense of ownership of what’s going on by being your partners in keeping the classroom a safe place,” McNeill added.

It’s December and, according to Ahmad, there’s been no instruction from the DOE or his school on how to use the purifiers. But whatever the issues, he added, “I just do what I can because I’m not there to fight about air, I’m there to teach kids.”

About the author(s)

Marcela Rodrigues-Sherley is a fellow at the Toni Stabile Center for Investigative Journalism at Columbia Journalism School.