Earlier this year, Josephine Okungu made a decision that broke her heart.

Since September 2017, she’d worked as a special education teacher at HeartShare’s Cuomo First Step Early Childhood Center. The Queens pre-school is publicly funded and privately run, serving children with disabilities whose educational needs can’t be met through public school programs. Despite having a master’s degree and several years of experience, Okungu earned less than $25 an hour. Still, it was a job she cherished.

“I loved going to class, working with our community,” she said. “My child went to the same school.”

But when Okungu’s husband lost his full-time job as a journalist last year, she had to reassess her income. Ultimately, she decided to leave HeartShare in January. Now, through her work with the state’s Early Intervention program, she continues to still support young children with disabilities or developmental delays — except that now she earns over $70 an hour, 30 hours a week.

“It comes to a decision between feeding my child … and doing the job that I love,” Okungu said.

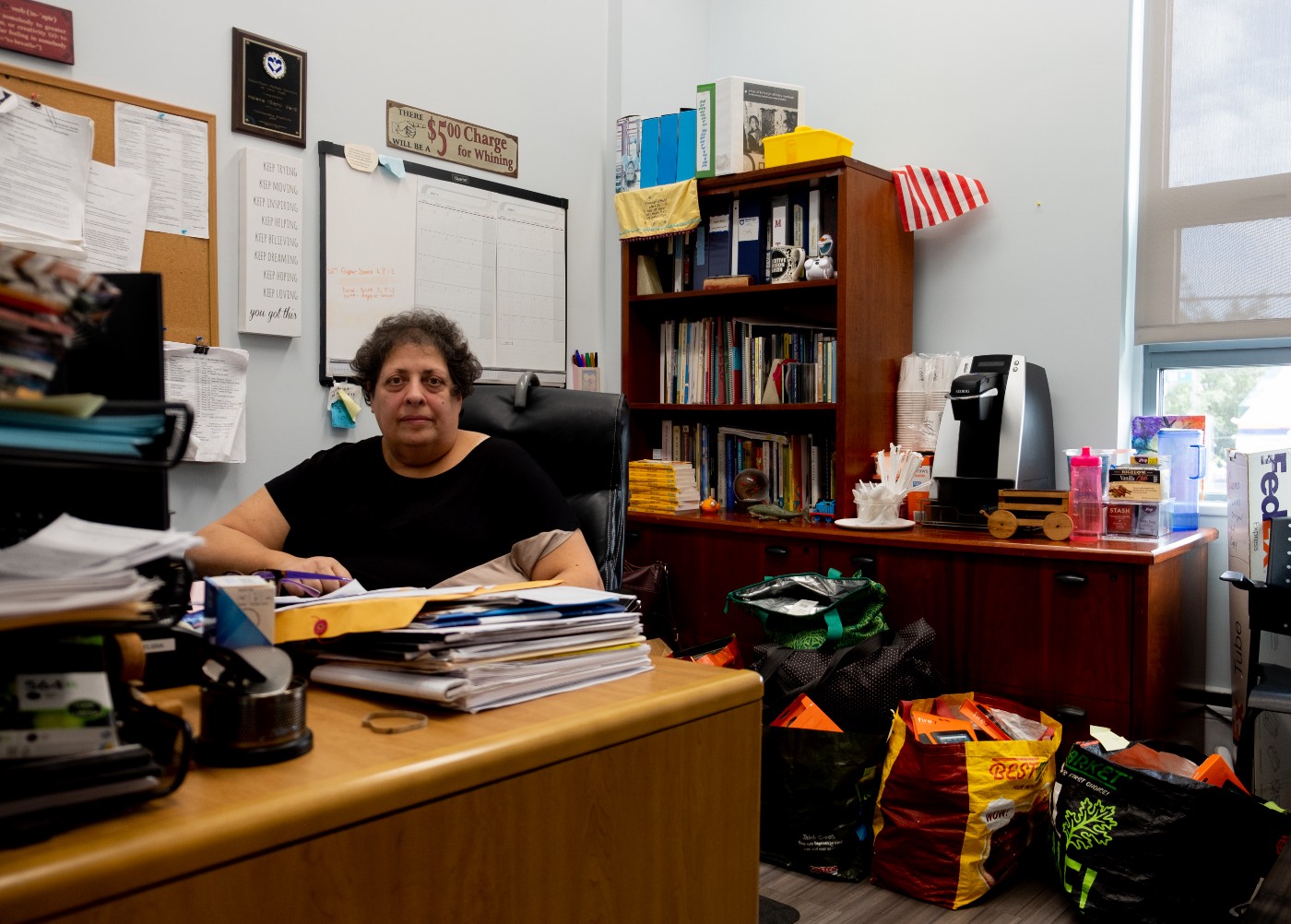

Having special education teachers and staff leave for higher-paying jobs has become increasingly common over the last decade, said Carol Verdi, HeartShare’s executive vice president for education services. Many go on to public schools.

Verdi would like to pay them more, but she can’t compete because of the state’s unequal funding policies. And while the Legislature unanimously passed a bill in June to address the gap, providers are still waiting for the governor to sign it.

According to the InterAgency Council of Developmental Disabilities Agencies (IAC), a coalition of providers that includes HeartShare, a certified teacher with five years of experience in special education schools can earn $51,000 for a 12-month year. A teacher with the same experience in public schools can get $87,000 a year for working 10 months.

In 2019, unionized and non-unionized community-based pre-K educators reached deals with New York City for major pay increases — including up to $20,000 — to catch up with public schools. But teachers in special education schools were left out because most of their funding comes from the state.

“You can’t blame people when they leave to go to a better opportunity, but it leaves our programs struggling to hire staff,” Verdi said.

In the past few months, she’s lost seven out of around 50 teachers. As a result, many staff members are covering more classes than expected, until HeartShare can make new hires. But that prospect remains elusive.

“My principals spend a good portion of the week interviewing, but nobody accepts the job once they hear the pay,” Verdi said. “It’s fruitless labor.”

Advocates and parents said that this staff turnover can be damaging to children with disabilities.

Maggie Sanchez, co-founder of a Facebook group for parents and advocates called Protect NYC Special Education, has a 12-year-old son with autism. Last year, she said, his class lost assistant teachers who were working on math and reading, which undid many of the gains he had been making.

“He wanted to get questions right, so not having that help was stressful,” Sanchez recalled. “It snowballed into anxiety, into nervousness and into his self-confidence going down. With the help, he would be able to do them in maybe an hour or so. Without the help, it took him hours.”

New York lawmakers are trying to address this disparity. A bill sponsored by Sen. John Mannion and Assemblymember Michael Benedetto would tie the annual growth in funding for special education schools to the public school’s rate. They pointed out that while public schools across New York are getting a $1.4 billion (7.6%) increase in a major category of state aid this year, special education schools are receiving a $85 million (4%) increase.

“We did encourage the state to make sure that [special education schools] were treated in a manner that public schools were. But unfortunately, that was not the case,” Mannion told Columbia News Service. “It’s unfair, it’s inequitable, and it’s unpredictable for them.”

This issue is not new. According to the IAC, the state provided only a 10% funding increase for special education preschools — compared to 46% for public schools — over the last decade.

Chris Treiber, the IAC’s associate executive director for children’s services, added that affiliated special education preschools saw more than 20% turnover and close to a 30% vacancy rate for certified teachers in 2019. He said the IAC did not run a survey last year over fear of the pandemic skewing the data, but the council is conducting one this fall. He expects a high vacancy rate, but a “not-so-high” turnover rate because “no one is coming” to replace departing staff.

“It’s very disheartening for the schools,” Treiber said. “And with the salary disparity, our teachers now are pretty much the lowest-paid teachers in New York City, which is just disgraceful.”

Special education schools are also going into the red, or closing altogether. Treiber said that over 60 such preschools have closed across the state, including more than 30 in New York City. These schools overall educate around 86% of the city’s preschoolers with disabilities.

“Teachers could go to other places to teach,” Okungu said. “But what about the students we leave behind? They’ll have to make do with whatever is there.”

The state’s Division of the Budget did not respond to requests for comment.

In the meantime, advocates and legislators are hoping that the bill can start to close these disparities. But, according to the New York State Senate website, it still has not reached Gov. Kathy Hochul as of November 9.

In New York State, the governor decides when a bill gets sent up for final approval. The governor’s office did not respond to requests for comment.

When the bill passed five months ago, Gov. Andrew Cuomo was still in office. In late July, Cuomo’s spokesperson Rich Azzopardi told NY1 News that it is “one of more than 900 bills passed the Legislature in the final weeks of session” and it was left “under review.”

Since then, legislators have attempted to renew attention to the bill.

Alongside Sen. Shelley Mayer and Sen. John Liu, Mannion sent a letter to Hochul on Sept. 27 with a “most urgent request for the approval.”

“She is a great listener and collaborator. She also really has focused on issues that have been not addressed, like childcare,” Mannion said, noting that during her time as lieutenant governor, Hochul co-chaired the state’s Child Care Availability Taskforce. “So I’m more optimistic than I was a few months ago.”

Okungu is cautious: “I’m hopeful it’s going to be positive. But at the same time, will I be surprised if they turn it down? No.”

About the author(s)

Alex Nguyen is a fellow at the Stabile Center for Investigative Journalism.