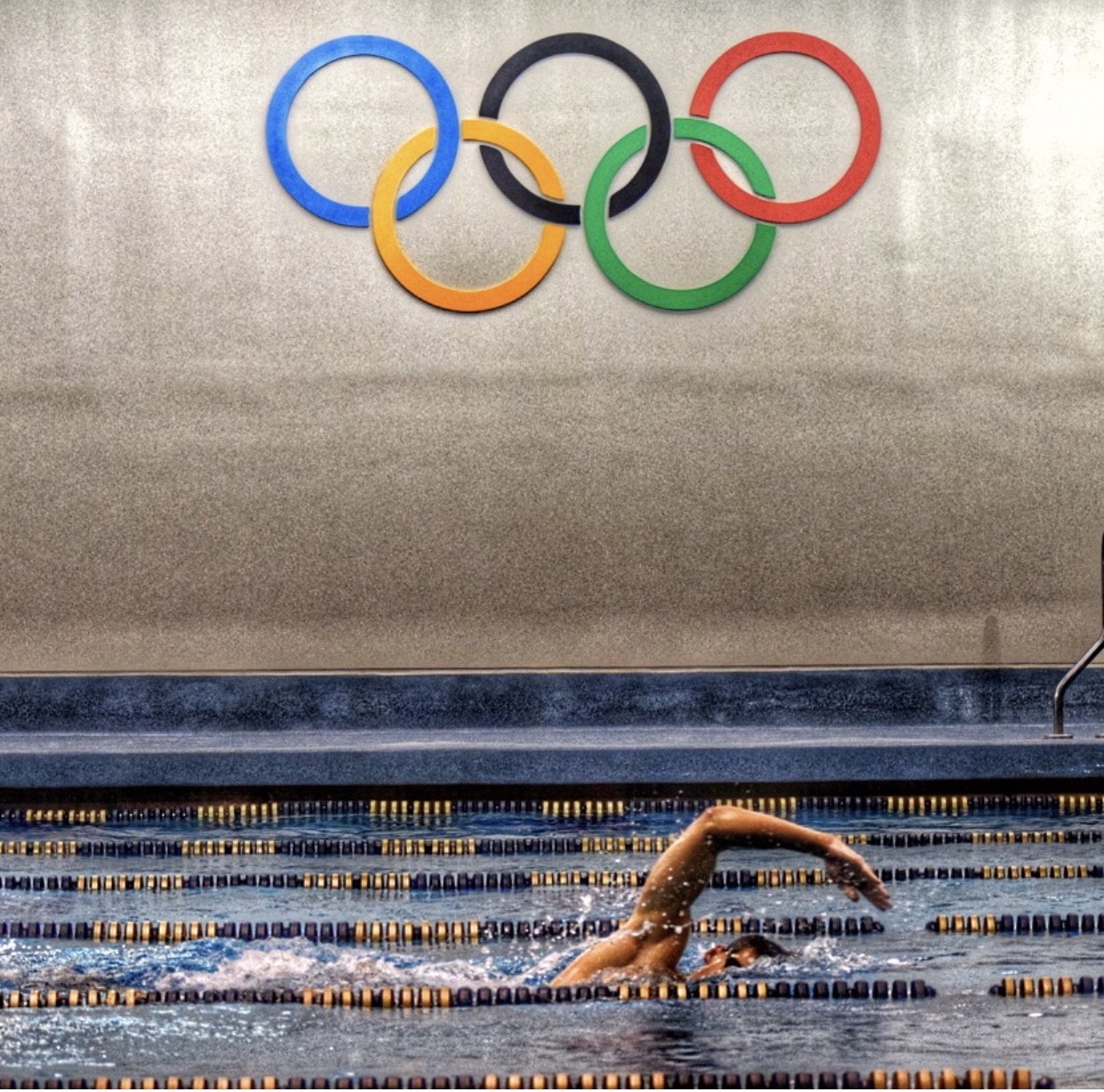

On Thursday morning, July 29, 24-year-old Caeleb Dressel was on the starting block at the Olympic pool in Tokyo listening for the starting gun. Back home in Charlotte, North Carolina, 26-year-old Matt Josa was watching. While other viewers saw a much-anticipated showdown between Dressel and USA teammate Tom Shields, Josa saw something far more personal.

Not so long ago, Josa shared the pool with Dressel and Shields. Over the years, he has defeated both men, as well as former teammates Michael Phelps and Ryan Lochte. He came close to swimming for an Olympic medal himself. But he knows better than anyone that close doesn’t count.

More than 4,000 athletes competed for a ticket to the Olympic games this year. Only 613 of them are competing in Tokyo. Some earned their spots by fractions of seconds invisible to the naked eye; others lost their chance by the same slim margin. Going to the Olympics can change lives. Not going can, too.

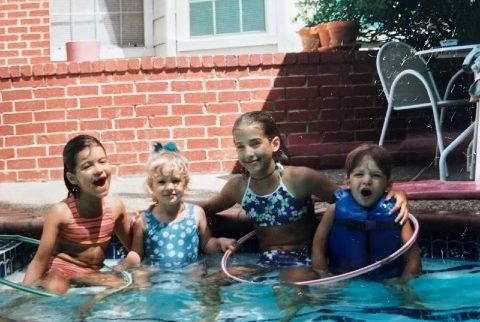

Josa has been swimming since he was 5 years old. As early as kindergarten, he announced to his class that he wanted to be an Olympic swimmer when he grew up. It wasn’t simply a childhood fantasy. Josa was willing to sacrifice for his dream. Josa, along with his sisters Brittany and Brooke, began swimming year-round in elementary school. By the time the three were middle schoolers, Josa and his parents had agreed that he could be homeschooled in order to spend more hours in the pool.

“He was extremely dedicated and passionate,” Brooke Josa recalled.

Consistent, too. “He didn’t … turn it on, turn it off,” said Jeff Dugdale, Josa’s former coach for both Team Elite, a high-performance swim training club, and Queens University in Charlotte, where he began his collegiate career. “That, combined with his dedication and fitness level, led to a young man doing very well at a young age.”

As Josa continued to compete, it became clear that he had national-level potential, and in 2012 when he was 17 he attended his first Olympic trials.

“I remember being like, this is it. This is what I’ve been waiting for,” he said. “I’ve had… a self-belief that, at least at that time, could transcend what I could actually do.”

The 2012 trials were a reality check. Josa was ranked 64th heading into the trials that year. He finished 48th. The experience was as humbling as it was motivating, and Josa went back to training with a vengeance. He practiced 30 hours a week. He began a specialized nutrition program designed to reduce inflammation, and he tracked everything he ate. He routinely gave urine samples to test his hydration levels.

Swimming consumed him, but the work had paid off. In 2013 not only was Josa selected for Team USA, he was also named captain. He finished third in the 100 meter butterfly at the World Junior Championships. He went on to win the 100 and 50 fly at both the 2013 U.S. Open and the U.S. National 18-under.

By then he was seen as one to watch in elite swimming circles. He became an NCAA All-American his freshman season at Queens University in 2014, and was named NCAA Breakout Swimmer of the Year for all divisions. The following year, he brought home five NCAA D-II titles and was named NCAA D-II Swimmer of the year.

Josa decided to forgo competing in the 2016 season at Queens in order to focus solely on preparing for the next Olympic cycle. In the months leading up to the trials he was ranked among the top eight male swimmers in the country, and the top 12 in the world.

On July 1, 2016, Josa won the preliminary Olympic trial heat in the 100M butterfly with a time of 51.61, making him the ninth-fastest swimmer in the world. Phelps, Dressel and Lochte finished 6th, 7th and 9th, respectively.

“When a younger kid has a big swim, it can change the whole trajectory,” Dugdale said.” They can be naïve enough to then become dangerous.”

The mix of exhilaration and joy left Josa dazed going into the finals. “I got lost in the moment,” he said. During his first lap he was distracted, thinking “This is years of training, thousands and thousands of laps, all coming down to these 50 seconds,” he said.

Then, somewhere in the middle of the last straightaway he knew he was in trouble. “In the last seconds, I suddenly realized, ‘I need to probably be here for this,’” he said. “I came back, but…”

It wasn’t enough. Phelps and Shields took the top two spots and thus, the tickets to Rio. Josa finished 6th.

The fallout came from all directions. “You have the self-disappointment because of how bad you wanted it and how hard you trained,” Dugdale said. “But you also have family, friends, fans that tell you how sorry they are. That’s another level of disappointment. That was something he hadn’t had to experience yet.

“Everything is tied back to identity,” he continued. “If you don’t make [the team], you think you failed, and that is going to change your identity. That can be devastating.”

The grief and self-doubt were new to Josa, but very familiar to Emily Klueh, former Team USA member and current U.S. Olympic and Paralympic Committee Mental Health Coordinator.

Klueh is now part of a U.S. Olympic Committee project to create a new framework around mental health services. While the program is barely a year old, the need has long existed.

“I wish this was in place earlier,” Klueh said. “We can’t change the past, but we can learn from it.”

One challenge, she said, is that athletes often exhibit symptoms when they are struggling emotionally.

“Mental health concerns like depression and anxiety often manifest differently in athletes than they do in the normal population,” Klueh explained.

Josa, for instance, went through a period of thrill-seeking behavior. In the months after Rio, during which he transferred to the University of California at Berkeley, he became reckless. He drove his motorcycle too fast and went on dangerous hikes. He nearly lost his life on several occasions. He was in denial.

“That’s one thing that sports give, that adrenaline rush, that high,” Klueh said. After a setback, some try to find that in other ways. “There’s a fine line,” she said, “between looking for an adrenaline rush that comes from sports and teetering on self-harm or other clinical behaviors.”

By spring 2017, Josa was mentally and physically taxed. Across the country from his family, still adjusting to his transfer to Berkeley and on a break from swimming following a disappointing performance during the NCAA Championships, he was feeling more isolated than ever. To make matters worse, Josa had been battling chronic Lyme disease since he was a child. Amidst the stress, it began to flare. He sank deeper into depression.

His nadir came one night in April 2017. “I gave myself 24 hours before I was going to do something,” he said, referring to his thoughts of suicide. “I prayed: ‘If you’re real, God, I need a sign. I probably don’t want to do this thing I’m thinking about.’”

The next morning, with no prompting, Josa awoke to eight phone calls and 13 texts, all from family and friends, all saying that they were praying for him. One of those was from Brooke Butler, head of the Athletes in Action (AIA) ministry at Berkeley.

“That was my proof,” Josa recalled. “I asked for a sign, and literally the next morning a so-called man of God reached out to me.”

In his 20 years of ministry, Butler had worked with many athletes dealing with a range of mental health struggles, but he vividly recalls his first meeting with Josa the following day.

“Hearing the depths of his devastation at that point was heart-wrenching,” Butler said. The two met weekly over the coming months, as Josa worked through his emotions and developed his identity outside of athletics.

“It’s human nature,” Butler said. “It’s not just an athlete, it’s all of us. Unless we find some kind of identity or worth outside of our performance, we’re going to be devastated one way or the other.”

Slowly, painstakingly, Josa began to rehabilitate his mental health. He finished his degree at Berkeley in 2018 and moved home to Charlotte. There he reconnected with his old coaching staff, including Dugdale, who had been with Josa since he was a teen. Josa picked up odd jobs, bartending and cleaning pools, to support himself as he continued to train. He was feeling more like himself and swimming faster than ever before.

Then, in March 2020, while Josa was attending a training camp in Colorado Springs, the U.S. Olympic Committee announced that, due to coronavirus lockdowns, the 2020 Olympics would be postponed.

This time the obstacle was not his mental health, but his bank account. Josa had been living off his savings. He had just enough money to get by until he could make the Olympic team and earn sponsorships. Now he faced an extra year of training, and that was time he literally could not afford.

During a 2020 swim meet he found himself standing in the grocery store when, he said, he “realized I couldn’t afford any of this…but I have to eat to perform.”

He went back to the pool, thanked Dugdale and told him that he did not have the money to support his quest anymore. He told his sister Brooke the same thing, and she suggested a GoFundMe campaign. Within the first hour, Josa had raised almost $1,000. The final total was $5,381. Josa began to cry; the city of Charlotte was going to send him to Trials.

On Friday morning, June 18 of this year, Josa stepped up to the starting block at the Olympic trials in Omaha. The feeling was both familiar and jarring as, once again, he stood on the edge of his dream.

He performed well in the 100m butterfly preliminaries, finishing 52.52, ranking 13th overall with the second-best split time among all nine heats. He had made it to the next race. But that evening, when Josa, Dressel and Shields were each among the 16 men who made it to the semifinal heat, he felt drained.

“Everything that was thrown to him this year,” Dugdale explained, “All those [stressors] increase cortisol levels quite significantly which then work against the body’s progression.” He swam one of his slowest races ever, a 53.03 in the semifinals, finishing just shy of last place.

It was a defeat that, at one time, might have broken him. But this time, when he touched the finish line, instead of shock he just felt relief.

“Getting to trials was just a huge blessing,” he said. After five years of fighting to get back, “I was just able to appreciate the experience,” he said. “Me getting to this spot was basically on the backs of other people.”

Josa said his heart is still in swimming, but he also said he’s at a natural stopping point.

It’s a common reckoning for elite athletes, said Dr. Jessica Bartley, who leads the mental health services department of the U.S. Olympic and Paralympic Committee.

Her staff works with athletes after loss, the situation Josa faced in 2016, and athletes who face the reality that their years of competition are probably over, as Josa is doing now, as he watches the Tokyo games from his stateside apartment.

“The reality is that a lot of athletes give up normalcy for sport,” Bartley said. “You practice every day, you travel, you miss events. And then it’s over.”

A successful transition into that new rhythm means embracing a new identity, Dugdale said. “Can it be refreshing to walk in and have nobody know you other than that you’re a good person before they ever find out that [you were] this superstar athlete?”

It can be, he said, but only for those who have fully closed the door. Josa said he will not be certain he has done so until the finals are completed on Saturday and he has watched the men who were nearly his teammates race on his TV screen without him.

“If I watch and there’s still that fire,” he said, “I’ll know I have to go another year.”

About the author(s)

Gretchen Tarrant is a print journalist currently based in Manhattan. Born and raised in Colchester, Vermont, she earned a bachelor’s degree in political science from Yale University while playing varsity ice hockey and lacrosse. Her past experience includes roles in finance, e-commerce, and marketing. An aspiring author and entrepreneur, she loves running, traveling and anything Trader Joe's. She can be found on Instagram: @gtarrantt, Twitter: @tarrantgretchen or reached via email: gretchen.tarrant@columbia.edu.